Anthills of Civilization

Metropolises are strange attractors - but not how you imagine them to be

Recently, I got a very thoughtful message from a kind reader and fellow writer, Lucas, which prompted me to write about the reasons and the possible future of urbanization. Quote:

“…the city was a story we were bound to imagine — “What if we all got together in one place? How crazy would that be? And now with this new hyper-gardening system, we could really make a go of it!” Thus, not one tribe of Takers wanting to get everything Under Control, and spreading the contagion worldwide by force; rather, a genuinely beautiful dream and natural product of the human imagination. Much more to say on this, but for now the following image will suffice: I imagine they got the idea from nature herself. A beehive, say. “What if we did something like that?”

The human imagination is a product of nature; and the city was an inevitable product of the human imagination, sooner or later. Therefore we can consider this whole story of civilization divinely ordained; and then we are obliged to ask — why? Could there not be some teleological explanation for why the Gaian system has chosen to condense its energy into this one species? Perhaps our cities are cells of a new organism, destined to establish a new harmony with nature? On this view, civilization, with all its violence and horror, is a means to an end. We just have to figure out what the end is.”

What an intriguing idea! Indeed, this question has bugged quite many of our archeologists and historians for centuries if not millennia. Despite all the hard work which went into digging up ancient cities and trying to fit the broken pieces together (both literally and figuratively) we are just starting to understand what brought these people together into one place. Perhaps we were looking in the wrong direction all the time?

Thank you for reading The Honest Sorcerer, and special thanks to those who already support my work; without you this site could not exist. If you are new here and would like to see more in depth analysis of our predicament, please subscribe for free, or perhaps consider a paid subscription. You can also support my work by virtually inviting me for a coffee, or sharing this article with a friend. Thank you in advance!

According to the latest archeological evidence cities are a more ancient concept than agriculture, states or kings. As the truly magnificent research done by David Graeber and David Wengrow shows — presented in their book, The Dawn of Everything — large semi-permanent settlements appeared thousands of years before we started to live solely on agricultural produce. These cities served as meeting points for tribes who lived most of their lives as nomadic foragers, only to gathered together periodically in these settlements for sacred rituals. (Okay, exchanging genes among tribes surely played a role, too.) These gatherings took place in the most abundant season of the year, when collecting food took little to no effort and great surpluses could be piled up. Evidence suggests that temporary kings were elected in some of these locations, who then established all sorts of crazy rules and norms for the festive season. The surplus energy (in form of food) was then used to build sacred monuments, such as huge mounds shaping serpents, earth berm pyramids or large stone structures such as the twelve thousand years old temple of Göbekli Tepe.

Many of these ancient cities, often housing thousands of people, served a purpose beyond ritual gathering and were inhabited all year round for centuries. Well before the advent of large scale agriculture and empires, these settled societies were largely egalitarian and self-organized. There were no city centers where elites lived in luxurious homes — all houses were pretty much the same. Agriculture in this prehistoric era, at least according to Graeber and Wengrow, was more like “play farming” — a side-hustle to foraging. The ancient city of Catalhöyük in present day Turkey was a prime example of this lifestyle. Evidence suggests that growing crops had more of a ritual role than providing a prime source of calories, which in turn still came from hunting and gathering.

That peaceful setup has changed forever with the appearance of the first purely agricultural societies in West Asia. Pushed into the marshes formed by the rivers Tigris and Euphrates in present day Iraq, tribes had to adopt a lifestyle based primarily on cereal crops. Since all the nearby hunting grounds were already occupied by other tribes, the first Mesopotamians had no choice but to adapt or die. The idea (and technology) of building cities was already a given to them, together with the knowledge on how to cultivate crops. The appearance of the first agricultural civilizations (literally meaning a society based on cities) thus was a disaster waiting to happen.

The massive energy surplus made available by agriculture, combined with the necessity to move into areas less amenable for foraging has led to — almost accidentally — the foundation of the first city states. It was the accumulation of a food surplus (in the form of grain storage) and certain groups’ ability to “guard” these, which has led to the formation of hierarchical societies, not a single person’s vision to establish a city in the middle of nowhere. From that point on the Genie was out of the bottle: the ecological disaster we call agriculture unfolded on a massive scale all across the Middle East. Entire forests were chopped down for firewood, building material and yes, more farmland. Top soil was eroded and vast areas were rendered into pastures, then into wastelands. Rain patterns have shifted as a result of this massive geoengineering project, turning once thriving ecosystems into deserts. With the sudden increase in food supply came a similarly sudden increase in population, and later the merger of these city states into empires, perpetuating ecological destruction.

“Forests precede civilizations and deserts follow them” — François-René de Chateaubriand (1768–1848)

Evolution, be it biological or cultural, was always driven by necessity and was made available by the right circumstances. If those circumstances were not right, or the species in question was not able to adapt, extinction followed. The easily verifiable fact that we didn’t go extinct in the past ten thousand years proves that we were able to adapt to drastically changed circumstances from the end of the ice age to a range of inhospitable areas we happened to migrate into — as all other lands were occupied by other members of our species.

Take note, however, how the stable climate of the Holocene made such adaptations possible in the first place: without a predictable periodicity of rains, growing crops was a hit and miss — not a reliable source of food. Had the climate not been stabilized ten thousand years ago, we would be most likely still living in small tribes collecting nuts and berries (and would be much happier as a result, but that was not one of the selection criteria.) So, while Homo Sapiens appeared roughly three hundred thousand years ago and developed language and culture at least seventy thousand years before our time, the circumstances for large scale civilizations beyond a few permanent settlements were simply not present for the better part of our past. That didn’t mean that during warm periods between ice ages (inter-glacials) we couldn’t developed civilizations — in fact this seems perfectly possible and frankly quite plausible — but sadly there is no evidence left of those ancient societies beyond myths and legends. Perhaps, they were washed away by the rising seas or simply left no permanent mark on the land they occupied. We will never know.

Be it as it may, access to energy played a pivotal role in the birth and lives of civilizations. Energy always was the currency of life, with money playing a mere transactional role. Plants collecting sunlight turned solar irradiation, carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and water from the soil into food calories — first harvested as nuts and fruits by foragers, then as grains by agriculturalists. In both cases however, it was the surplus (the portion remaining after feeding the people doing the harvesting) what made cities possible in the first place. In the case of periodic settlements the hunter gatherer population coalesced around a temporary recurring surplus of fruits, nuts and prey animals (thriving also on the abundance of food). In the case of the first permanent settlements people gathered in places of unusual year round abundance of food (such as Catalhöyük), then later moved into places where starting agriculture was necessary for survival. The larger the surplus was in a location, the larger cities became.

Viewed through the lens of physics and ecology, human societies (from hunter gatherers to industrial nations) have always been part of a much bigger system converting sunlight into muscle and brain power. We are as part of the web of life as we were ten thousand years ago. The only difference is, that technology made us forget this simple fact. We still depend on oxygen and food produced by plants, as well as pollinators and a range of other species making agriculture possible… Not to mention potable water filtered by rocks and temperatures regulated by forests and oceans — among many other things. We are an integral part of this world, not separate entities acting freely according to their whims. Although we tend to view ourselves (especially in the West) as autonomous agents, circumstances, evolution and the availability of energy played a much bigger role in our history than we would like to believe. According to the founding myths of our modern, and many ancient civilizations alike, individuals exhibiting a great talent for technology and statesmanship shaped history single-handedly. That is, however, nothing but patting ourselves on the shoulder for things which required the hard work of many generations before us and the sacrifice of the living world. Only if we let go of the popular notion that our species is “special” or “apart” from the rest of Nature and that the rules of the game does not apply to us because we are so “intelligent”, can we understand the situation we have found ourselves in.

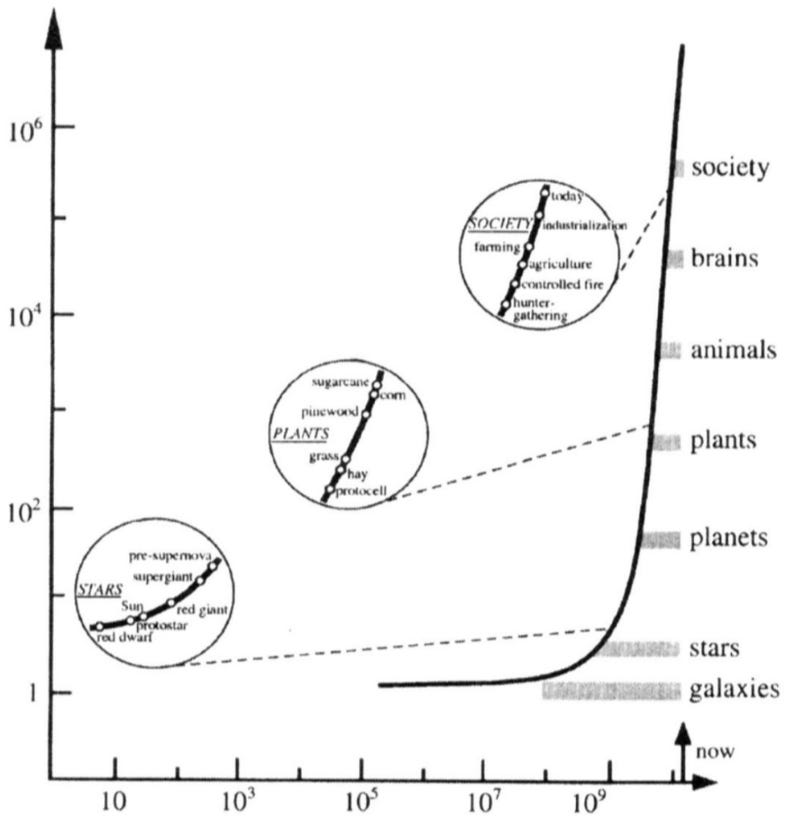

Self-organizing around surplus energy, our cities and civilizations are more like complex adaptive systems, than governance structures designed by clever humans. Borrowing a term from dynamical systems theory cities are ‘strange attractors’ — a direction towards which a system tends to evolve over time, despite exhibiting chaotic behavior all along the way. From this perspective our societies are much more akin to birds forming a flock, ants building a mound or hydrogen molecules coalescing into stars — not something designed consciously… Or, for that matter with a purpose, other than maximizing the energy throughput of the system and thereby outperforming neighboring cities, states or ecosystems in a race for more land and resources. Depending on the availability of surplus energy, we form tribes and temporary settlements, and if more is available, then create cities and states. Then, if still more energy is found, we found supranational organizations and word spanning empires. If there were no limits to the amount of surplus energy available to society, or there were no detriments to the careless release of that massive energy surplus, it would be logical to assume that we could one day become a multi-planetary species. Limits, however, do apply.

Complex adaptive systems, such as the human ecosystem, use concentrated sources of energy and raw materials and turn them into waste heat and trash (pollution). And while natural ecosystems do this by relying on sunlight alone and recycling almost every tiny bit of material through a process honed for billions of years, humans waste both energy and resources. With the mass adaption of agriculture, we have eroded the topsoil and reduced previously rich and diverse ecosystems into lifeless deserts. We’ve repeatedly ruined our environment and had to look for a method to keep on going with civilization. Relentless growth was not only a desire of the elites, but a sheer necessity to keep pretending that we can continue with our unsustainable approach to life. The alternative was, as always, civilizational collapse due to the depletion of resources and the destruction of ecosystems.

After ravaging the entire planet in search for arable land and minerals, we have ended up with having to drill and dig for ever more fossil fuels to prevent stagnation and eventually a forced retreat into a more sustainable arrangement. So far we haven’t found a panacea to our predicament, only made things worse by tapping into a store of ancient sunlight deposited as a byproduct of an otherwise almost perfect recycling process. What we’re actually doing in this moment of planetary history by releasing gigatons of ancient carbon is overloading the globe’s current recycling mechanisms, and using that temporary energy abundance to mine previously inaccessible metal ores, wood and other resources — only to turn those as well into waste. Since we are talking about squandering a one time inheritance, though, this virtually guarantees that we will eventually come out dirt poor at the end of this bonanza; left both without viable, easy-to-get energy sources or minerals and a habitable planet conducive to our civilizational practices.

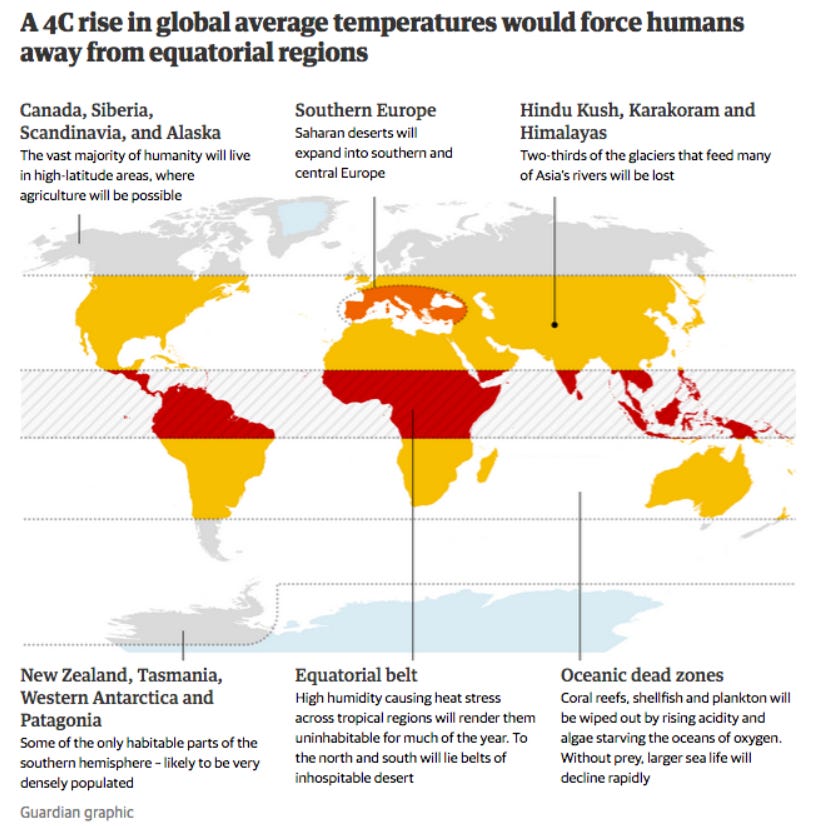

As a result of all these hundreds of years of slashing and burning and the release of all that ancient carbon, the planet’s climate is rapidly shifting back to where it was millions of years ago, well before the first humanoid creatures appeared on this pale blue orb. That means temperatures 5 to 10 degrees higher on the long run; climate change won’t stop at the end of the century, or just because we run out of stuff to burn. It will take centuries if not a millennia for the climate to settle, and based on current projections it will be nowhere close to be as hospitable to human life as it ever used to be. Yes, that means that the ongoing sixth mass extinction will continue, the Amazon will turn into a savanna, and after a few cooler centuries in Europe (following the collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation) much of the land on the planet will become uninhabitable. Sea levels will rise to sink all our coastal cities, or turn them into hot and humid salt marshes plagued by bacteria and billions of mosquitos.

That means, that if we survive the coming centuries as a species, we will have to find a new way of living, mostly on the lands and forests within the Arctic circle. Again, this is not something which could or will happen overnight, the collapse of this global civilization will take several decades (if not a century), while the above mentioned climatic changes will certainly take centuries to fully unfold. This calamity will result in a long slow march North, combined with a massive depopulation over the centuries. However, whatever civilization emerges once the rubble stops bouncing and when the climate settles into a new normal, its complexity will remain a function of available surplus energy.

Lacking the power of fossil fuels and minerals amenable for artisan mining techniques, it will be practically impossible to rekindle another industrial revolution, though. Wood and peat could be the prime source of energy and stone could be the raw material to build cities from. Much akin to its Roman predecessor such a civilization — if it ever comes to be — will be based around maritime travel, trade and fishing. This time, however, instead of doing this along the shores of the by then steaming hot Mediterranean Sea, we could see an empire arising along the shores of the lukewarm, ice free Arctic Ocean.

Of course, that presupposes we could somehow reinstate some sort of a regenerative agriculture on the taiga and would be able to produce surplus food necessary to build and maintain permanent settlements. If not, that means we either go extinct in the process (which is more likely than I would prefer), or somehow became nomadic tribes of herders and hunter gatherers again — which I find highly unlikely amidst a widespread civilizational, climate and ecological collapse wiping out all large wild animals. But who knows… Many things are possible — except for this exuberant lifestyle to continue.

Until next time,

B

The Honest Sorcerer is a reader-supported publication. Please consider a subscription or perhaps buying a virtual coffee… Thanks in advance!

I’m deeply skeptical that the Graeber-Wengrow thesis was simply an extension of Graeber’s anarchist-socialist ideology. But even on its own terms, the argument strains credibility. At best, it overgeneralizes from a few outliers—sites like Göbekli Tepe and Çatalhöyük—which were exceptional, not representative.

A seasonal gathering place for ritual, feasting, or drunken mating festivals is not a city. And calling these sites “egalitarian” just because we don’t see palaces or elite homes is misleading. Hierarchy can exist without stone monuments—through ritual authority, monopolies on knowledge, or informal power structures.

The broader idea that cities emerged from a neat, gradual accumulation of agricultural surplus has become a lazy meme. In reality, subsistence farming today rarely produces any substantial surplus—so why assume early farmers, with worse tools and less knowledge, did better?

Omer, Moav and Pascalis (2020) offer a more realistic account: surplus didn’t arise from abundance, but from coercion. Grain is storable, visible, and taxable—making it ideal for appropriation by elites backed by weapon-wielding thugs. Marvin Harris noted that the very idea of “surplus” is a projection—modern assumptions about wealth and efficiency read backward onto cultures that had no such framing.

The reality looks messier, more contingent, and far less egalitarian than Graeber and Wengrow wanted it to be.

Nowadays people relocate to the city because that's where the jobs and money are. When I was young, I chose not to do that. In my mind, the tourism industry in rural Quebec offered a better quality of life than the big city economy. As far as I'm concerned, civilization is rural and dotted with villages.