Running on Empty: Copper

How peak copper arrived and went completely unnoticed

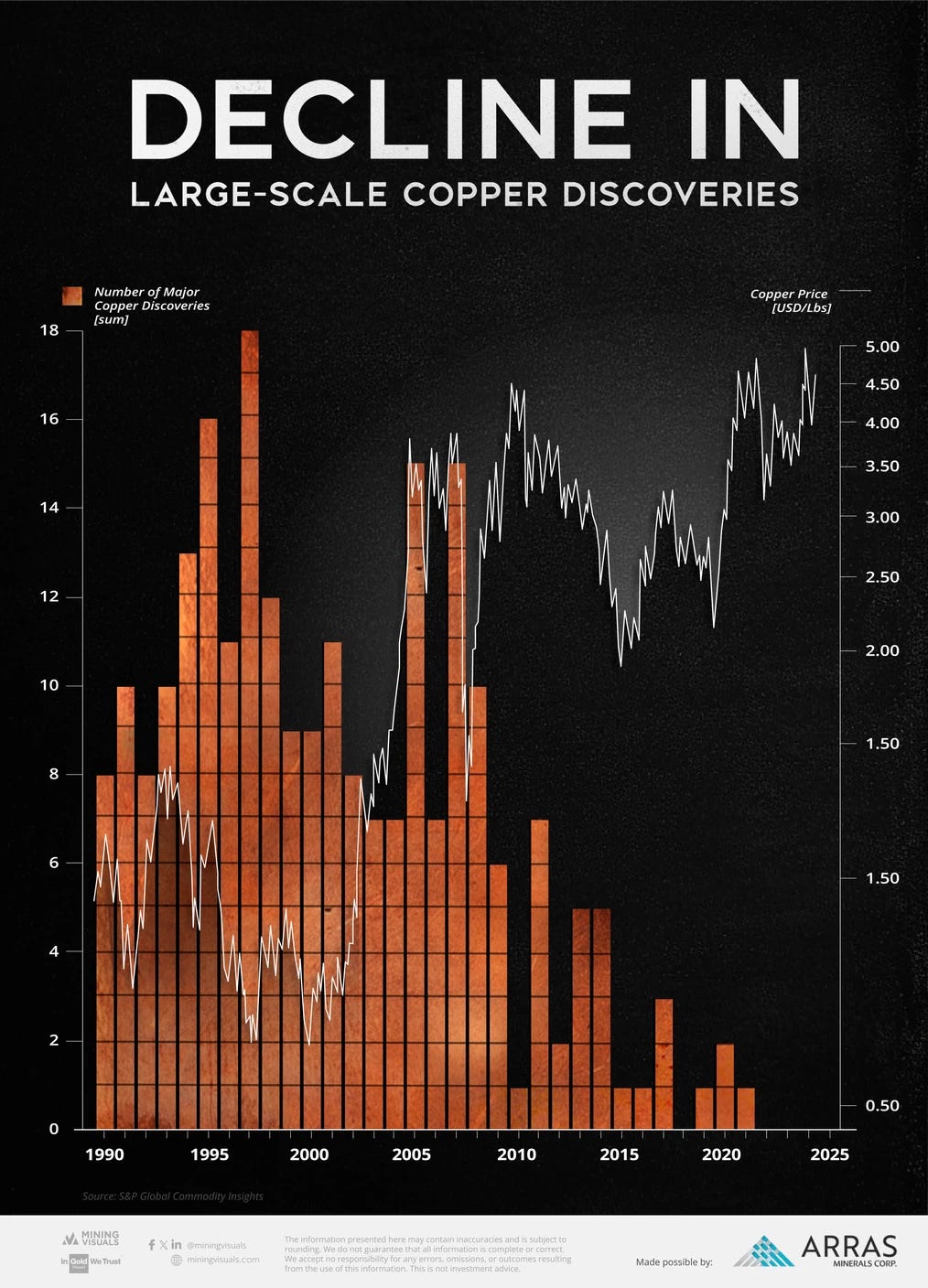

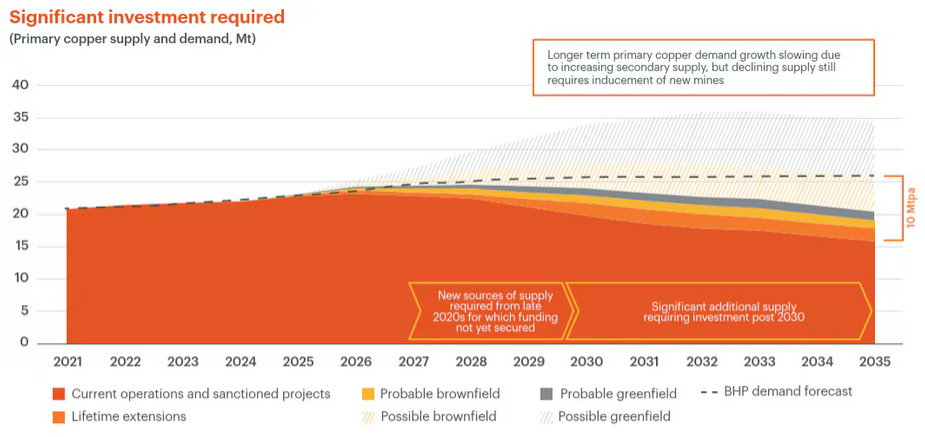

The price of copper has reached new record highs due to supply constraints. And while the Energy Information Agency expects global copper production to reach an all time high later this decade, they also warn that by 2035 the world will be in a whopping 10 million ton shortfall. Australian mining giant BHP also estimates that the world will produce 15% less copper in 2035 than it does today, as copper discoveries grind to a screeching halt and existing mines deplete. The signs of an imminent peak and decline in copper production could not be any clearer.

Thank you for reading The Honest Sorcerer. If you value this article or any others please share and consider a subscription, or perhaps buying a virtual coffee. At the same time allow me to express my eternal gratitude to those who already support my work — without you this site could not exist.

Insatiable demand

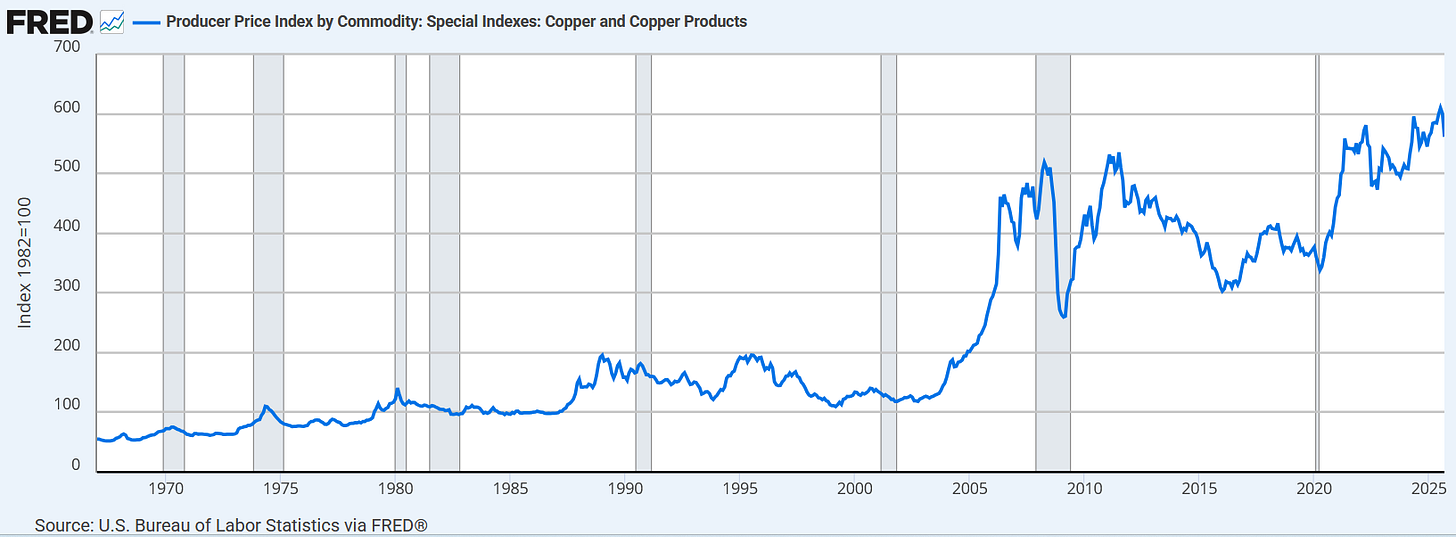

The price of copper has reached new record highs this weak, exceeding $11,600 per ton on the London Metal Exchange (LME) on Friday. Ostensibly this was due to a large withdrawal of the metal from LME warehouses earlier this week, but if you look at the long term trend, there is clearly much more at play here. The price of copper is trending upwards for decades now. Global financial giant UBS has just raised its price forecasts aggressively, predicting that copper will cost $13,000 per ton by December 2026. What is going on here?

Simply put, we are on a collision course between tightening global copper supply and demand fueled by electrification and most recently: AI data centers. Copper is an essential component in everything electric due to it’s high heat and electrical conductivity, surpassed only by silver. Copper wires can be found in everything from power generation, transmission, and distribution systems to electronics circuitry, telecommunications, and numerous types of electrical equipment—consuming half of all mined copper. The red metal and its alloys are also vitally important in water storage and treatment facilities—as well as in plumbing and piping—as it kills fungi, viruses and bacteria upon contact and conducts heat very efficiently. Thanks to its corrosion resistance and biostatic characteristics, copper is also widely used in marine applications and construction, as well as for coinage.

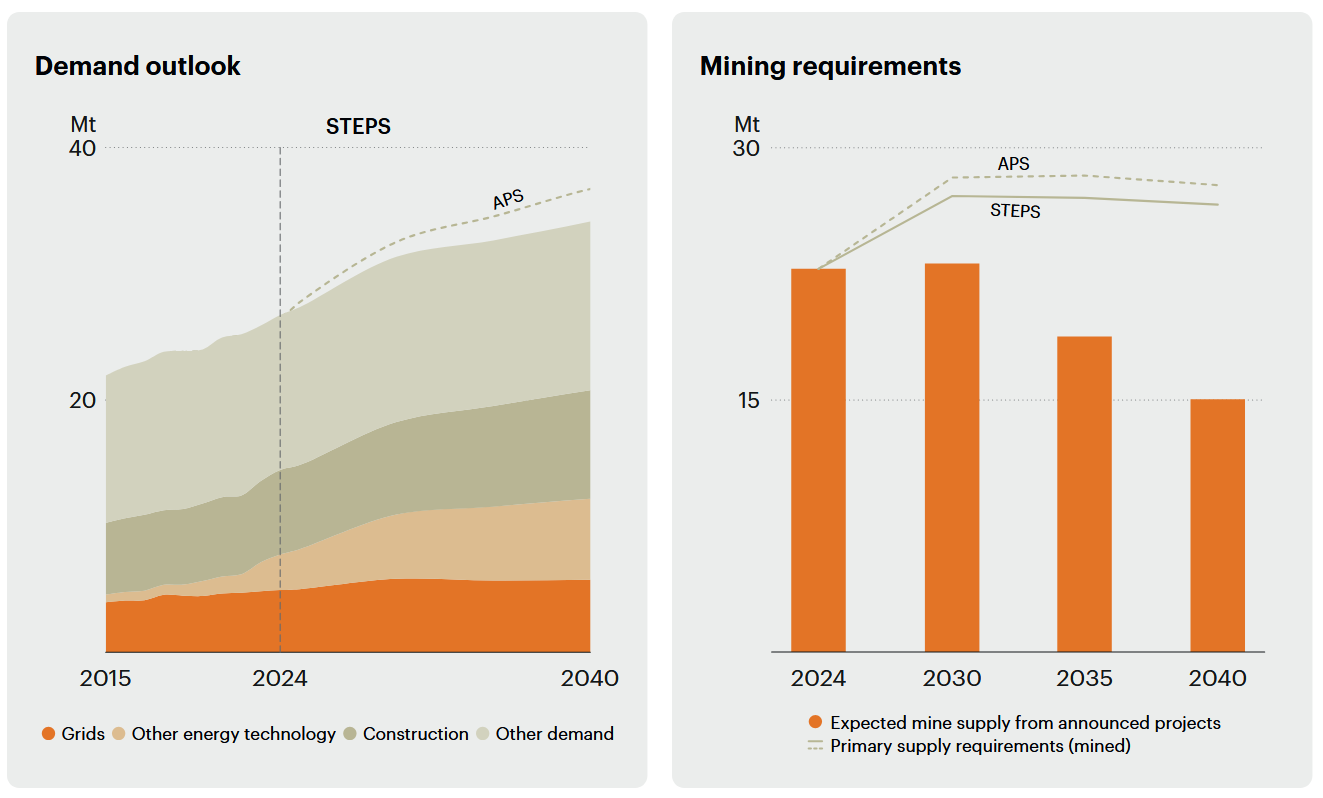

Growth in copper demand thus comes from both ‘traditional’ economic growth—especially in the Global South—and the energy supply addition from “renewables”. (Not to mention the extra demand from EV-s and data centers, or energy efficiency and conservation measures, such as smart grids, LED lighting, and heat pumps.) Problem is, that the generation and transmission of low carbon electricity requires more copper per megawatt than conventional fossil fuel power plants. Offshore wind farms, for example, take around 11 tonnes of copper per megawatt to build—that is over 5 times as much as gas-fired power plants. Onshore wind and solar are also more copper-intensive, at around 1.7 and 1.4 times, respectively. In addition, the capacity factors of wind and solar power are also much-much lower than fossil power. This means that we need to install 5-10 times more renewable power capacity, just to generate the same amount of electricity we used to do with natural gas or coal. Together with the necessary grid extensions, batteries, transmission lines, transformers etc. the copper demand raised by “renewables” will grow orders of magnitude greater than that of traditional, but highly polluting fossil fuel generation.

On the traditional economic growth front, demand can also be expected to grow dramatically. Perhaps it comes as no surprise, that China continues to be the world’s largest consumer of copper with its massive industrial output—accounting for nearly 60% of global copper consumption, and dwarfing the US in the second place at 6%. Looking ahead, though, India can be expected to rapidly overtake the United States to become the third-largest source of refined copper demand, with Viet Nam also emerging as a major contender for copper. Industrialization, infrastructure development, population expansion, urbanization and relocating plants out of China are all driving forces for the growth in refined copper consumption in these regions. So, even as China’s economy matures and Western industries decline, there are a number of nations with an insatiable demand to take up the slack. No wonder UBS expects global copper demand to grow by 2.8% annually through 2026 and beyond. Australian mining giant BHP’s estimates are not much smaller either:

“Putting all these levers together, we project global copper demand to grow by around 70% to over 50 Mt per annum by 2050 – an average growth rate of 2% per year.”

Infinite growth on a finite planet

Problem is, copper doesn’t grow on trees. It can only be found in certain geological formations, taking millions of years to form. In other words: it’s a finite, non-renewable resource. Humans have used copper for over 11,000 years, and as usual we went after the easiest to find and extract deposits first. Naturally, when all you have is a pickax and basket, you don’t start to build large open pit mines. Our ancestors thus went after copper nuggets found in riverbeds first, collecting lumps with 35% copper content, or perhaps climbed a little uphill and hammered away rocks with a still considerable amount of metal in them. Then, only when these resources were depleted, have they started to dig caves and build underground mines, following thin seams of copper in the rock.

Today there is very little—if any—copper left in the world, which could be mined using artisan techniques. As we ran out of those easy-to-find, easy-to-get ores with a high metal content, we increasingly had to rely on machines to haul away the mountains of rock overburden and to bring up copper ores with an ever lower metal content. And thus we face a predicament: what shall we do when there is no more easy-to-get copper resources to be found? See, what little is discovered today, lies beneath miles of rock or in the middle of a jungle, and takes more and more money, energy and resources to get. The chart below tells it all:

As you can see, finding more copper is not an issue of price. Only 14 of the 239 new copper deposits discovered between 1990 and 2023 were discovered in the past 10 years. Even though the industry would be willing to pay top dollar for each pound of metal delivered, there is simply not much more to be found. Copper bearing formations are not popping up at random, and there is no point in drilling various spots on Earth prospecting for deposits, either. The major formations have already been discovered, and thus the ever increasing investment spent on locating more copper simply does not produce a return.

And this is where our dreams and desires diverge from material reality.

Despite rising copper prices, exploration budgets remained below their early 2010s peaks, further reducing the possibility of finding new deposits. Companies were prioritizing extending existing mines rather than searching for new ones, with early-stage exploration dropping to just 28% of budgets in 2023. Copper mining is an extremely dirty, water intensive and polluting business. No wonder local communities are doing everything they can to avoid another mine being built next to their village—further reducing the options for extending supply. Global copper reserves were approximately one billion metric tonnes as of 2023, and due to the reasons listed above, this figure cannot be expected to grow much larger—unlike demand.

According to this study a full transition to an alternative energy system—powered entirely by a combination of “renewables”, nuclear and hydro—would require us to mine 4575 million tons of copper; some four-and-a-half-times the amount we have located so far. To say that we have embarked on a “mission impossible” seems to be an understatement here. Even if we could extract every ounce of copper in the ground in the coming decades, we could only replace 22% of our ageing fossil fuel energy system with an all electric one, then would be left wondering what to do with the remaining 78%… We clearly have a serious math problem here. And this is not just a vague theoretical issue to be solved sometime in the future. As discoveries ground to a screeching halt and existing mines slowly deplete, suppliers of copper will find it increasingly hard to keep pace with growing demand in the years ahead.

At first, falling inventories and persistent supply risks will keep market conditions extremely tight. This is where we are at the moment. Persistent mine disruptions, like an accident in Indonesia, a slower-than-expected output recovery in Chile and recurring protests affecting operations in Peru are already putting strains on supply. No wonder UBS has trimmed its refined copper production growth estimates to just 1.2% for 2025… It gets worse, though: tariffs, trade and geopolitical uncertainties, together with droughts, landslides and other climate change related concerns are all threatening to worsen the copper supply outlook in the years ahead. The balance between supply and demand is already very fragile, and can be expected to become feebler still. Hence the price rally we see unfolding.

In the medium term, however, we are facing an even bigger issue. We are rapidly approaching an inflection point, where mined copper supply begins to fall—irrespective of demand. Even as global mined copper output reached a record 22.8 million tons in 2024, the IEA expects global supply to peak later this decade (at around 24 Mt) before falling noticeably to less than 19 Mt by 2035, as ore grades decline, reserves become depleted and mines are retired. Despite the potential contribution from African copper, new greenfield supply will struggle to make up the difference, as it takes 17 years on average till a mine starts production from discovery, and as new mines cost more and more to open. In Latin America, average brownfield projects now require 65% higher capital investments compared to 2020, approaching similar levels to greenfield projects. Starting a mine from scratch, on the other hand, is getting even more challenging, experiencing delays and facing long lead times. Major copper projects including Oyu Tolgoi (Mongolia) and Quebrada Blanca 2 (Chile) have experienced significant delays and cost overruns.

Simply put, we have run out of time, capital, resources and energy to prevent a massive shortfall in copper production by 2030.

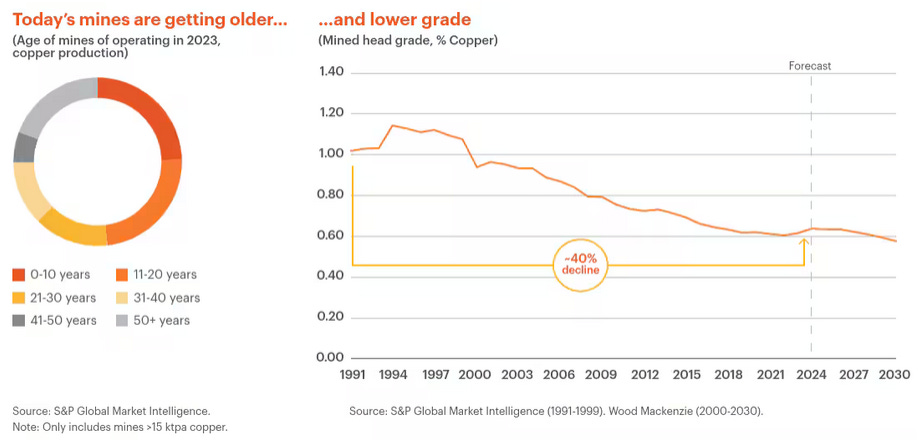

The silent killer: declining ore grades

“The trend of declining copper head grades is well established and unlikely to be reversed,” says consultancy firm McKinsey in its research. Referring to the metal content of mined ore going into a mill for processing, researchers at McKinsey pointed out the crux of the predicament. As we dug out all the high grade ores, what’s left requires increasingly energy intensive and complex methods to get. BHP, a world-leading Australian multinational mining company, found that the average grade of copper ore has declined by 40% since 1991.

Needless to say, this process had—and continues to have—profound implications. Instead of bringing rocks with 1% copper content to the surface (which is already bad enough in and of itself), miners now have to haul 0.6% grade ores on their trucks. This worsening trend puts excess strain on both the shoveling (excavators and dumper) fleet, and on the ore mill itself. To bring an example, imagine you are driving a dumper track capable of hauling 100 tons of crushed rock from the mining pit. In 1991, each load you emptied into the ore mill contained 1 metric ton of pure copper, waiting to be liberated. Forty years later, the same truckload of ore contained just 600 kg (or 1322 pounds) of the red metal. Needless to say, your truck didn’t consume less diesel fuel and spare parts just because your mine has run out of high grade ores: you still had to haul 100 tons of rock in each round.

However, as years passed, you had to drive into an ever deeper mine, going further deeper for the same amount of rock, while burning through untold gallons of ever costlier fuel. Meanwhile, the mill had to crush this ever lower grade ore into an ever finer dust (1), in order to liberate the ever smaller particles of copper. What’s more, as the McKinsey report points out, less capital-intensive oxide ore bodies are now being exhausted across the globe, leaving miners with more labor and energy-intensive sulfide ores (2). Is it any wonder then that the production costs of copper mining just keeps rising and rising?

This is indeed a perfect storm for copper mining. Falling ore grades, leading to extra fuel and electricity demand in hauling and milling copper bearing rocks. The depletion of copper oxide mines, and their replacement with sulfide deposits requiring extra equipment and tons of energy to process. Rapidly decreasing rate of new resource discoveries, combined with increased capital costs and complexity for expansions and new projects—all deterring investment. Increased flooding and drought risk, threatening extraction both in tropical humid climates as well as in the deserts of the Andes. Trade wars, tariffs, regulations, geopolitical tensions… Is it any wonder then that BHP has came to the same conclusion as the EIA, showing us a nice little graph depicting that which must never be named: peak copper. Even BHP, for whom copper mining is one of the primary source of revenue, estimates that existing mines will be producing around 15% less copper in 2035 than they do today, leading to a whopping 10 million ton shortfall in mined copper compared to demand.

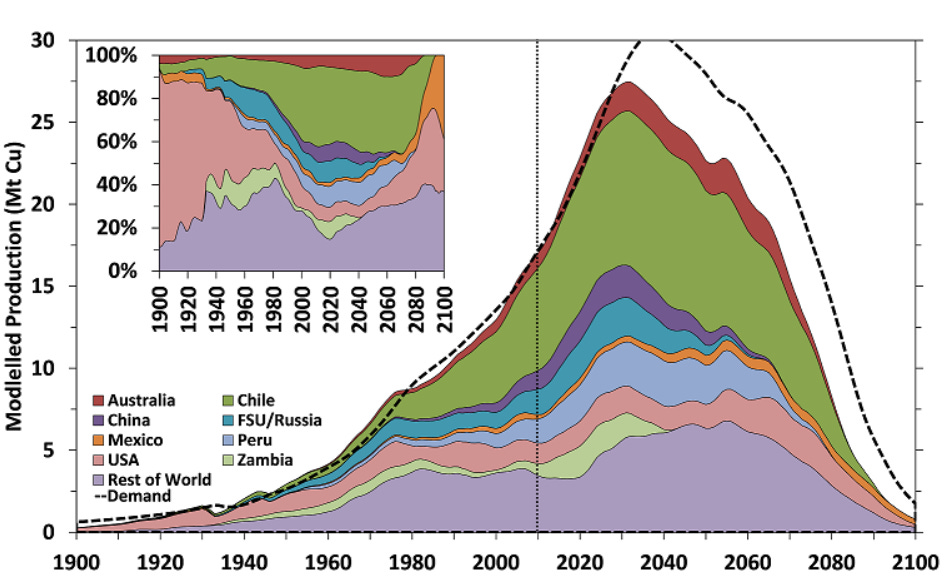

Not that this was not foreseen. The idea of peak copper, or the time when annual copper output reaches its all time high, then begins to decline, is not something new. The math is not terribly complicated, and so it was done more than ten years ago already. Although scientists at Monash University (Melbourne, Australia) somewhat overestimated peak production (putting it at around 27 Mt in 2030), they came pretty close. As things stand today, we will most likely reach peak mined copper supply somewhere between now and 2030, at 24-25 million tons per annum. And all this comes on top of humanity reaching peak liquid fuel supply around the same time—isn’t it ironic…?

But, but… But then we will recycle!

Almost all of the articles and studies referenced in this essay refer to a “wide variety of supply- and demand-side measures” needed to close the gap left behind by peak copper. Measures include: “stimulating investment in new mines, material efficiency, substitution and scaling up recycling.” If you’ve read this long, for which I’m eternally grateful, allow me to be a little blunt here, and let me call this what it is: BS.

First, we “must” build out a new energy system, before we run out of coal, oil and gas—let alone before we could start recycling old electric vehicles, wind turbines and the rest (3). Electricity currently provides 22% of our energy needs, the rest, especially in heavy industries comes from burning fossil fuels. (Which by the way is a show-stopper on its own, as electricity cannot replace these fuels at scale, especially in high heat applications needed to build solar panels, wind turbines and yes, refining copper.) Knowing the amount of copper reserves, and the lamentable, sorry state of discoveries, it is utterly inconceivable that we could build out even half of the necessary “renewable” power generation capacity before we completely run out of the red metal, even if we turned every scrap metal yard upside down and inside out.

Most of the copper in circulation is already serving the needs of electrification, or used in applications where copper’s antimicrobial and heat conducting properties are essential. The lifecycle of these products is measured in years and decades, BHP assessed that the average life of copper in-use is around 20 years. So at best we could recycle what we have manufactured around 2005, when global copper production was half of what we see today… What’s worse, much of this old scrap is never recovered. According to BHP’s estimate only 43% of available scrap was collected and recovered for re-use in 2021, falling to 40% in 2023 as “lower prices, slowing economic activity and regulatory changes acted as headwinds.” And we haven’t even talked about the rise of “scrap nationalism, aiming to preserve the local use of secondary material, and placing restrictions on cross-regional waste trade.” Let’s be realistic, recycling won’t be able to fill the gap. At best, it can slow down the decline… Somewhat.

Bah! Who needs copper anyway, when we have so much aluminum?!

Have you thought about how aluminum is made? Well, by driving immense electric currents through carbon anodes made from petroleum coke (or coal-tar pitch) to turn molten alumina into pure metal via electrolysis. Two things to notice here. First, the necessary electricity (and the anodes) are usually made with fossil fuels, as “renewables” cannot provide the stable current and carbon atoms needed to make the process possible. Second, all that electricity, even if you generate it with nuclear reactors, have to be delivered via copper wires. And this takes us to our next saving grace: substitution, referring to the replacement of copper by other materials, such as aluminum, plastics, or fiber optics.

Substitution and thrifting (the reduction of copper content or usage in products), on the other hand, “would require significant design modifications, product line alterations, investment in new equipment, and worker retraining.” Since copper has some unique advantages, making it difficult to substitute or thrift in many end-uses, this is far easier said than done. Let’s take conductivity. The biggest loss by far in any (and every) electric equipment is the waste heat generated by internal resistance of wires and the myriad of electric components. It’s not hard to see why replacing copper with lower quality materials (like aluminum) in wires, and other critical components comes at a serious drop in performance — if it’s technically possible at all. Except for high voltage cables hanging in the air from tall poles, it’s hard to think of any application where the excess heat generated by electrical resistance would not damage the system to the point of catching fire, or degrading its performance considerably.

So when copper prices rise beyond the point of affordability, we won’t see a significant increases in substitution or thrifting activities. Instead, financially weaker companies will go bankrupt, markets will consolidate and consumers will be priced out en masse. Just like with oil, we will face an affordability crisis here, first driving prices sky-high—only to see them plunge to new depths as demand disappears. Peak copper and peak oil will hit us like a wave of Tsunami, amplifying each other through many feedback loops. (Just think about diesel use in copper mines, or copper use in energy production.) Despite the many warnings we are going into this storm completely unprepared, and have done practically nothing to prevent the waves crashing over us.

Conclusion

The window of material opportunities to maintain—let alone grow—this six continent industrial civilization is closing fast. Not 500 years from now, but starting today and slamming shut ever faster during the decades ahead, as all economically viable reserves of fossil fuels and copper run out. This is a geological reality, not something you can turn around with fusion, solar, or whatever energy source you fancy. We have hit material and ecological limits to growth, and mining in space is not even on the horizon. Trying to switch to “renewables” or building AI data centers so late in the game is thus not only technically infeasible but ill-advised, accelerating resource depletion even further and bringing about collapse even faster. Instead of hoping that technology will somehow save us, we immediately need to start working on and implementing a ramp-down plan on the highest governance level, before the chaos over “who gets to use the last remaining resources on Earth” ensues us all.

Until next time,

B

Thank you for reading The Honest Sorcerer. If you value this article or any others please share and consider a subscription, or perhaps buying a virtual coffee. At the same time allow me to express my eternal gratitude to those who already support my work — without you this site could not exist.

Notes:

(1) The lower the grade (metal content) of an ore, the smaller the grains of copper entrapped within the rock are. Smaller grains mean a more homogeneous structure, resulting in harder rocks, requiring more energy to crush… Now, combine this with the fact that we would need to mill those rocks into ever smaller pieces—to free up those tiny copper particles—and you start to see how energy consumption runs rampant as ore grades decline.

(2) The difference lies in what comes after milling copper ore into a powder. You see, copper in oxides is soluble, allowing direct extraction through leaching. During this process dilute sulfuric acid is percolated through crushed ore piled on impermeable pads, dissolving copper into a solution which is collected, then purified via Solvent Extraction (SX) and recovered as pure metal by Electrowinning (EW). The wide-spread adoption of this leach - solvent extraction - electrowinning (SxEw) process from the mid-1980’s unlocked previously uneconomic, low grade oxide ores, and now accounts for 20% of mine supply. However, it cannot be used on copper sulfide ores, which require more complex and energy intensive physical separation methods. This type of extraction involves froth flotation after fine grinding, followed by roasting, then smelting (to form a copper-iron sulfide matte), and converting (removing iron to get blister copper)—all done at a vastly greater energy, equipment and labor cost.

(3) Many parts and components built into wind turbines, solar panels and electric vehicles are not designed with recycling in mind. In fact, the industry tends to cramp as many features into one part as it can, in order to reduce assembly costs. This approach often results in parts with monstrous complexity, permanently gluing and welding sub-components made from various materials into one, with plastic often injection molded around them. Put more simply: they are nearly impossible to recycle, and due to their complexity, need skilled manpower to disassemble first, before the excess plastic can be burned off or dissolved in aggressive solvents. Toxic waste (fumes and liquids) are often generated during this process, not to mention the need for excess energy and the complicated logistics network involved in performing this feat. This is why recycling companies tend not to bother with electronic components and dump faulty parts on poor countries in South Asia and Africa.

Sources:

Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025—IEA

Copper Demand Set to Hit 37M Tonnes by 2050—Can Supply Keep Up?—CarbonCredit

BHP Insights: how copper will shape our future—BHP

Slow but steady: declining ore grades jeopardize the mining industry’s sustainability—Rough&Polished

Red Metal Fired Up: The Outlook for Copper—CME group

Bridging the copper supply gap—McKinsey

Modelling future copper ore grade decline based upon a detailed assessment of copper resources and mining—published on Dr Stephen Northey’s website

UBS Outlook: Copper to Hit $13,000 by 2026—Mining Visuals

Assessment of the Extra Capacity Required of Alternative Energy Electrical Power Systems to Completely Replace Fossil Fuels—Geological Survey of Finland, Circular Economy Solutions KTR Espoo

Thank you for another reality check on resource limits. It is interesting how all these non-renewables are reaching peak simultaneously. Not entirely unexpected for anyone that read TLTG years ago. The unsettling part is the accuracy of the Club of Rome's report. Living in and around fishing communities and seeing the demise of commercial fishing over the last 30 0r so years it isn't a big shock. I believe it was stated to be around 2025 for the end of commercial fishing on the open seas. Well that seems about right, there are few fisheries left that can be considered viable. Most are now subsidized by .gov in one way or another. Even that won't be enough soon. Raw resource extraction will likely become nationalized just before it stops completely on a "supply the global market" side on the equation.

Another problem associated with copper is simply theft. As its price rises, it becomes increasingly profitable to steal copper wires or pipes, thereby destroying very expensive equipment and installations and disrupting transport, communication, electricity, and other networks.

All these installations, often located in remote but easily accessible areas, must be protected. This entails additional maintenance and operating costs.

For example, cables used to charge electric cars at charging stations are regularly stolen because they are fairly easy to cut and can contain about €10 worth of copper. But replacing one can cost around €1,500!

As our societies literally cannibalize themselves, we may soon find ourselves in a situation where it will no longer be affordable to keep a number of existing networks operational. Not to mention building new ones...