Living in small homes built entirely from locally available resources and using manpower alone is not a fairy tale. However, it will take an awful long time and a lot of hardship till we get to that point… again. This is how the story of building one civilization after the other based entirely on non-renewable resources always ends, and it won’t be any different this time either.

Thank you for reading The Honest Sorcerer. If you value this article or any others please share and consider a subscription or perhaps buying a virtual coffee… At the same time let me express my eternal gratitude to those already support my work — without you this site could not exist.

After a couple of deep-dive articles on human energy consumption — and before leaving for a holiday break — I suggest to take a broader look on where we headed as a global civilization. And while many argue that there is no ‘we’ let alone a ‘global civilization’ to talk about, at the end of the day almost each and every one of us serve the same globalized extraction scheme. Except for the very few entirely self-sustained indigenous villages and tribes scattered around the globe, many of us give our labor to feed the globalized human system with raw inputs (food, energy, minerals etc.) or working on and with technologies consuming those resources, turning them into products and services and ultimately: waste. None of this would be possible without global trade and, of course, access to these essentials. Thus from the poor boy sacrificing his health in a Congolese cobalt mine to the high tech worker in Texas using that metal to build batteries from, or from the roughneck extracting the blood of this Earth to the farmer burning it as fuel in Mexico, ‘we’ are all part of one big ‘civilization’ — for a lack of a better term.

As a direct consequence to our increasing reliance on technology we as a civilization / economic super-organism / species (pick your favorite) have become totally dependent on non-renewable resources for our continued existence on this planet. Again, unless you are living in one of those very few tribes scattered around in the wilderness — which is highly unlikely since you read this on a screen — you, too, are dependent on this system to a greater or lesser degree. If you, just like me, work with metal tools or burn any amount of fossil fuels, perhaps use electricity or buy anything in a shop, you are part of that global extractive system. And what’s the problem with that? Well, beyond the pollution it creates, our technology uses non-renewable materials processed with non-renewable energy. And while its tempting to believe that so-called “renewables” harness the power of the Sun, these technologies, too, are built from non-renewable materials processed with non-renewable energy.

Our food production, too, has become largely dependent on a range of one-time resources: from fertilizers made from natural gas, phosphate rock and potash to diesel engines, ships and trucks ‘our’ global food system uses up a one-time inheritance of easy-to-get minerals, metals and energy at a frenetic pace. So far it managed to feed 8 billion of us, and who knows it might be able to feed even 10 billion or more. For now. But what happens when the amount of one-time resources harvested each year start to dwindle? Again, unless you live in a food garden cultivating your crops with a wooden stick, you are dependent on this system delivering resources to production plants world wide — to a greater or lesser degree, of course.

The obvious “problem” with such a reliance on non-renewable materials and energy is that all such resources deplete one day. While economists, mainstream scientists and academics believe that everything is fungible, in reality we are already using the entire periodic table of elements and all what nature has to offer. “Then surely, technology will unlock even more of those! Earth’s crust is full of metals and other minerals — enough to last thousands of years!” While that might be factually true, practically we face an insurmountable limitation here. Out of the billions and billions of tons of ores in the ground only a tiny-winy portion is accessible to us. The rest lies too deep, or is of a much lower quality — i.e.: they’re not worth going after.

Contrary to common wisdom citing human ingenuity, it was the profligate use of fossil fuels (diesel trucks and excavators and an immense amount of heat from natural gas and coal) what allowed us to extract and process the amount of materials we use today. People used to mine copper ore with a pickax and a bucket in the bronze age, dug deeper in the middle age only to begin using ever bigger machines in the industrial age; opening up ever larger pits and moving the extracted metal using ever larger ships across the surface of this planet. This is how we dug mining pits as deep as the Grand Canyon... Not by using our clever intellect, but by the sheer power of fossil fuels — just take a look at these monstrosities and the gigantic machines serving them.

Unfortunately for us — but more fortunately for Nature — wind turbines, solar panels and batteries lack the energy density and continuous power needed to carry on with mineral extraction at this scale. Like it or not, mining and processing the metal ores essential to build “renewables” with “renewables” alone is an absolute non-starter. There is, however, a much bigger problem lurking beneath the surface than how do we power the mining operations of the future.

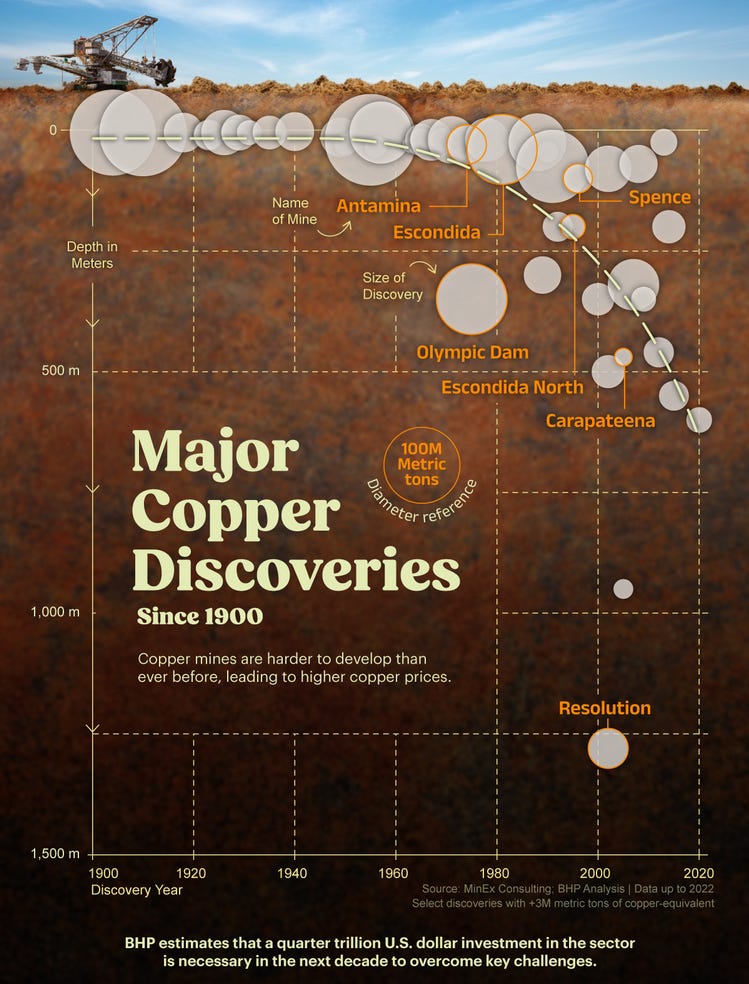

Thanks to our modern civilization’s insatiable hunger for resources, we have started to run out of all easy-to-access minerals. Now we have to dig considerably deeper to extract a considerably smaller amount of considerably lower grade ores. Take copper, a metal essential to everything electric from EV-s to nuclear power plants, for example. The chart above, courtesy of one of the world’s biggest mining company, BHP, tells it all: long gone are the days of large discoveries. What remains are those ever smaller batches of copper found deeper and deeper in increasingly unfavorable locations. If you were wondering why even mining giants are reluctant to invest in new mines, look no further for an answer.

And it’s not just about the accessibility, but the quality of minerals retrieved: we have reached a point where declining ore grades began to jeopardize the mining industry’s sustainability. This, ladies and gentleman, is how resource depletion looks like — not a sudden crash but a slowly accelerating process gaining momentum over decades. And while, in theory at least, we could retrieve minerals from asteroids, mine the ocean floor or skim them from seawater, there are practical limitations. These technologies, just like the jump from artisan mining to industrial scale extraction, would require an energy expenditure orders of magnitude larger compared to our present methods and come with an even greater environmental destruction than before.

The depletion of mineral resources implies that we would constantly have to grow our energy consumption in an exponential fashion — just to stay in place and produce the same amount of stuff as yesteryear. Now, if you consider that we still get 91% of our global energy supply from fossil fuels, and realize that all so-called “alternatives” (nuclear, wind, solar etc.) rely a 100% on coal oil and gas to make, you start to appreciate that we are facing a predicament here, not a problem with a solution. You see, fossil fuels are just as prone to depletion as copper: we have already used up the best, highest quality, easiest-to-get portion of these polluting energy sources, and now we have to expend more and more energy every year just to satisfy present demand. And we haven’t even began to transition away from coal, oil and gas in earnest.

The predicament we face is that we have started to run out of the easy-to-get stuff, leaving ‘us’ with fossil fuels providing an ever lower energy return on investment — even as mineral reserves would require more and more fuel to extract. Unless we manage to dramatically expand our energy throughput every year, we will slowly lose our ability to access remote reserves of metal ores needed to build “renewables”, nuclear power plants or as “simple” a thing as a combined harvester or tractor used to increase agricultural productivity. This is a very-very slow process which, nonetheless, is already underway — as witnessed by western nations, who had to give up their heavy industries as they ran out of affordable metals and energy. China could, so far at least, grow its energy consumption (and thus its industrial output) but they, too, face the same predicament. The world’s largest coal consumer and the country having the fourth largest coal reserve in the world is struggling to keep up with demand. Thanks to its insatiable hunger for energy China has barely got 35 years of coal left, indicating that the world’s largest economy by energy consumption faces an imminent peak and decline of coal production. (Again, they will start losing mines to depletion one-by-one, eventually leading to a gradual fall in output well before the last colliery closes its gates.) So when Chinese carbon emissions peak, we will know what’s the reason behind.

While many pin their hopes on a “circular economy,” recycling non-renewable minerals without losses is impossible, and what’s worse: not even technically desirable. Products, buildings and large structures require a pretty large amount of ‘virgin material’, as the many impurities and unknown material properties of various metal scraps make it impossible to guarantee structural strength and safety. (The same goes to solar panels and wind turbines, just sayin’.) Non-renewable resources are called non-renewable for a good reason: once we use up the economically accessible portion of these minerals, nothing remains but scattered low-grade, hard-to-get stuff. This means, that once this industrial era is over, there will be no second industrial revolution. Once we use up all remaining raw materials, or run out of the economically viable portion of fossil fuels needed to get and process them, we will lose our ability to build new infrastructure, new roads, new cars, new power lines, new bridges… That means that we will have to recycle what we already have into ever lower quality, ever lower spec products till we simply have to discard them.

Admitting this is not pessimism — it is acceptance, the accommodation of reality. The natural world doesn’t care about our feelings anyway. If we keep destroying and depleting its resources, it will act accordingly and eventually put a limit to human desires. Climate change, species extinction, pollution, or resource scarcity are thus all symptoms of this entirely human-made civilizational predicament. No society can hope to build all its technology on non-renewable materials and brag about it for much too long. Let’s face it, our civilization is deep into overshoot territory: we use much more materials and natural resources than what can be regenerated, while releasing much more pollution which could be absorbed by Nature. This civilization, just like the ones preceding it from the Romans to the Mayans, lives on borrowed time. And now, that time is up.

Admitting that we are already in the opening phase of a slow, protracted systems collapse is not ‘doomism’ nor akin to past prophecies preaching the end of times. It’s the result of logical analysis considering the data and facts presented above. In order to continue hoping that technological civilization could somehow continue one would have to deny at least some of the realities discussed here and in the many scientific publications on the subject. This also implies that any plan to “solve” our planetary overshoot predicament or any of its symptoms by throwing even more technology at it is a fool’s errand. Colonizing space, together with pollution reduction policies, decarbonization, a steady-state economy, de-growth etc., are all fairy tales we tell ourselves. As all of the economy from resource extraction to manufacturing and agriculture depends on rapidly depleting stocks of easy-to-get non-renewable mineral and energy resources, it is mathematically impossible to maintain a steady state or contract the economy without crashing it.

The only more-or-less sustainable lifestyle on this planet is a hunter-gatherer one. This is not a romanticization of the past: it was a tough and sometimes rather short life. That however doesn’t mean that we have another choice on the long run. Collecting nuts and berries, fishing and hunting within the biological regenerative capacity of Nature provided us with food, shelter and clothing for hundreds of millennia, even as Earth entered and left numerous ice ages, with temperatures shifting by as much as 10–15°C from one decade to the next. In other words: it is the only time-proven method for our species’ survival.

The same cannot even hoped to be told about ‘our’ techno-industrial ‘civilization’, nor about agricultural societies 100% dependent on a stable climate and predictable rainfall patterns. Even a minute swing up or down could upend this civilization, just as it did to the ones before. And while our technology giving us world trade prevented hunger so far in the West, the future with less technology will inherently become more fragile with every passing year. Not because ‘we’ wanted so, or because of greedy corporations, evil dictators or what have you. No. It’s because the very idea of building a civilization entirely on the extraction of non-renewable materials to depletion was unsustainable from the get go…

What we got on our hands here and now is the outcome of a predicament we entered ten thousand years ago. After repeated iterations of the many civilizations ravaged the entire planet, having reduced wildlife populations and the size of natural ecosystems to a mere fraction of their original size, there is no return to the caves, spears and bows either. At least not this century or the next. This civilization has no other option than to go through a long, protracted but nonetheless radical simplification. Even though we will eventually have to leave all modern technology behind, this won’t happen from one day to the next, nor voluntarily for that matter.

As we slowly run out of economically viable resources, production of minerals and fossil fuels will begin to decline, leading to a diminished industrial output and financial / political collapse across many nations. Yes, there will be a tremendous upheaval. Repeated rounds of deindustrialization will, however, ensure that we will no longer need that much coal, oil and gas — leaving more resources for food production and preventing widespread hunger. Wars, and territorial changes will become more likely as well, but the prevailing theme behind our slow-motion systems collapse will remain the same. De-industrialization will make large scale warfare relying on tanks, rockets, planes and ships impossible. Once large weapons stockpiles start to run low, nations will have to return to the negotiating table. The growing disparity between Eastern and Western powers show, that this is going to be a highly uneven process.

Self-organizing itself around energy and minerals production, our civilization is more like a complex adaptive system than a single unitary governance structure designed by clever humans. In fact, the global political order is falling apart exactly because of that: decided on by humans harboring a fantasy of infinite economic growth, together with the permanence of western supremacy, it was bound to fail from the get go. The drastically changed energy and material production reality is no longer accurately reflected in the current global political setup. The US, together with Europe, is rapidly losing its prominence as it can no longer produce goods, weapons, energy or raw materials in adequate quantities and at a competitive price. Truth to be told, Western nations have always lived off of the surplus produced by the rest of the world. Just take a look at the 500 year long history of colonization, corporatism and “free trade” with large numbers of natives dying as a feature, not a bug.

Thanks to the influx of large amounts of raw materials from their colonies, western nations were the first to industrialize. After two world wars, the loss of their colonies and the depletion of their own resources, their relative share in the world economy began to shrink visibly. Now, that both energy and material production is far greater outside than inside western nations, the political landscape has began to change, too. That doesn’t mean that China or any other power on the ascent is any better — just different. The main theme underpinning the new multi-polar world remains the same: extract as much material and energy as you can, as fast as you can. As we have seen above, this can only end one way: overshooting the material and energy resource base, then collapse. Again, no country, nation or “world order” can build its technology on non-renewable materials and hope to brag about it for much too long. China did nothing special in this regard: just out-competed the US in this race to the bottom.

Then why don’t we do something about it? Simple: those who did realized the folly behind amassing material wealth and returned to or remained with a forager lifestyle were simply wiped out by those who organized their societies around ever increasing material and energy extraction. And as we have seen above, as resources depleted (be them fossil fuels, minerals or fertile soil) expansion became a must. Borrowing a term from dynamical systems theory a higher energy and material throughput has become a ‘strange attractor’ for all civilizations — a direction towards which a system tends to evolve over time, despite exhibiting chaotic behavior all along the way. And that chaotic behavior in our case meant economic downturns, crises, wars, pandemics and the like. Temporary setbacks notwithstanding, maximizing the energy throughput of the system, and thereby outperforming neighboring nations and ecosystems in a race for more land and resources, has become the name of the game.

Systems (be them physical, biological, economic, political etc.) which use energy the most efficiently always out-compete other, less efficient systems. This process ultimately leads to all available energy and resources being used up — hence the name: the Maximum Power Principle — a phenomenon first described by mathematician, physical chemist, and statistician Alfred Lotka a hundred years ago. In our case it meant that foragers were out-competed by agriculturists, who were in turn were out-competed by industrialists burning fossil fuels. Each step represented a jump in energy and resource consumption. Social complexity, science, technology, GDP growth were all downstream to this ever higher appropriation of energy and raw materials, eventually leading to the formation of world spanning empires. First the Dutch, the British, then the American led “rules based order”— each bigger and more powerful than its predecessor. Since we are rapidly approaching planetary limits when it comes to further increasing our energy and material throughput, it is doubtful we will ever see a world spanning empire again.

Our current path as a global civilization is wholly unsustainable, and thus will not be sustained for much too long. Before we could begin our long descent back to a more sustainable lifestyle, the current system has to collapse, though. Thanks to the maximum power principle it will not and cannot give up power until it exhausts all other options and folds under its own weight. Only then can we begin to charter our way towards a new equilibrium with Nature and begin the long healing process. This will naturally involve a need to redevelop counterbalances to our desires and finding the wisdom to say no to things which we could otherwise do. The regular redistribution of wealth, farmland or fishing patches, not to mention debt jubilees and potlatch (giving away or destroying wealth or valuable items) are all good places to start. Greenland’s recent policies are serving us with a good example, but I’m afraid it will take an awful long time for the rest of the world to realize that humanity’s short affair with industrial civilization has indeed entered its final chapter with no sequel planned.

Until next time,

B

Thank you for reading The Honest Sorcerer. If you value this article or any others please share and consider a subscription or perhaps buying a virtual coffee… At the same time let me express my eternal gratitude to those already support my work — without you this site could not exist.

Instead of the flippant directive of “learn to code” for those who lose their jobs in the technology maelstrom, it will be “learn to compost.”

Buy the best hand tools that you can find and learn how to use them. Teach your grandchildren how to do things by hand. Find or make a community. The long road down has started, try not to be left behind.