What's Missing In This Picture?

Or how to be a techno-optimist by ignoring reality

As I mentioned in my last post, this past week I was attending and giving a talk at a conference on the future in Budapest. The event was superbly organized and went really well — it was an honor to participate. I also had the luck of having a fantastic audience asking highly relevant and smart questions, and the luck of meeting and making new friends there. We decided to work on future projects together, starting with a new platform and experimenting with different formats. But for now, back to the topic of today’s article. Despite the fact that my time was rather constrained this week, I still wanted to react to a presentation shared with me by a kind reader. It was titled: The Electrotech Revolution — The shape of things to come, jam-packed with tons of very interesting stuff and a curious graphic to talk about.

Thank you for reading The Honest Sorcerer. If you value this article or any others please share and consider a subscription, or perhaps buying a virtual coffee. At the same time allow me to express my eternal gratitude to those who already support my work — without you this site could not exist.

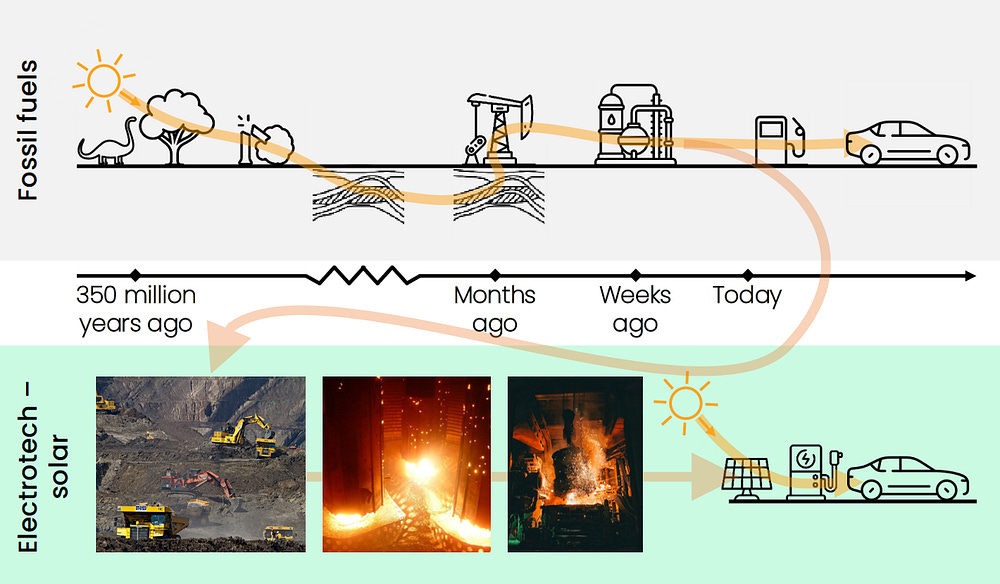

The report on the “Electrotech Revolution” was produced by Ember, “an independent energy think tank that aims to accelerate the clean energy transition with data and policy.” According to the core message of the document “electrotech” will inevitably overtake fossil fuels in their role as our primary source of energy supply and use. This will not only solve our climate predicament, but will also make us more efficient, affluent and prosperous. What’s not to like? Well, just take a good hard look on slide number 10, and try to guess what’s missing from the picture:

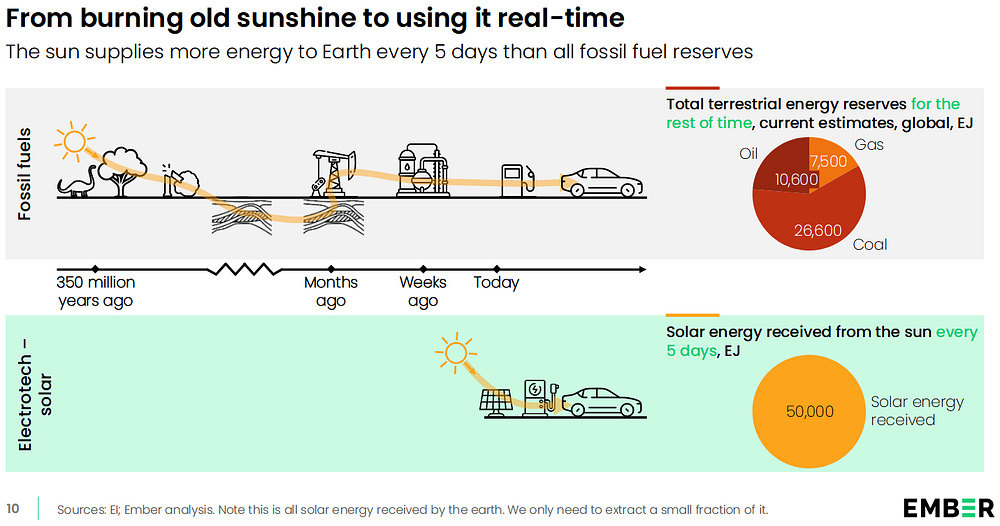

The fossil fuel part of the story looks just about right, despite being a bit oversimplified. Coal, oil and gas reserves are indeed stores of ancient sunlight, converted by plants into organic matter and cooked to perfection in Earth’s oven over hundreds of millions of years. Electrotech, powered by the Sun directly, on the other hand, promises to cut the dinosaurs together with their planetary cooking apparatus out of the picture, and provide clean, green, abundant and practically infinite energy on demand. Too bad that this for all intents and purposes is nothing but a big fat fairy tale. Not a single word, image or graph presented in the Ember document talks about, or even mentions, this:

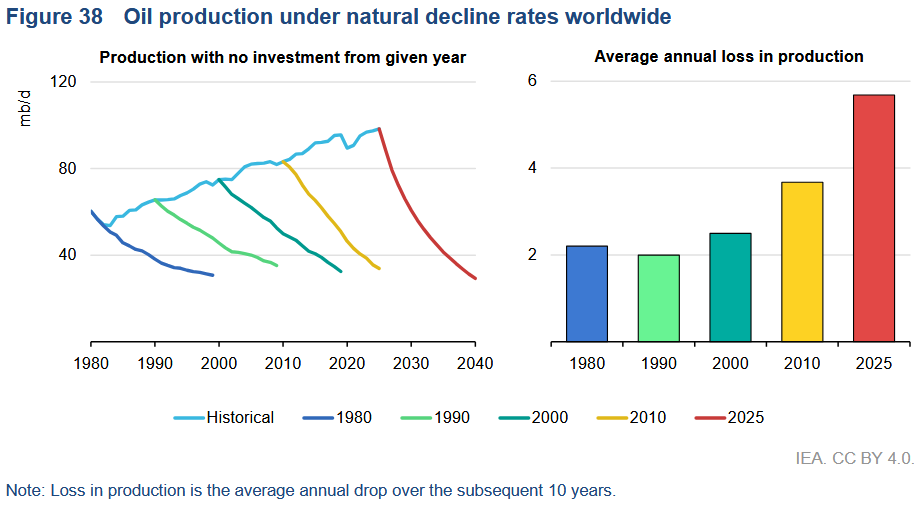

Nor this for that matter:

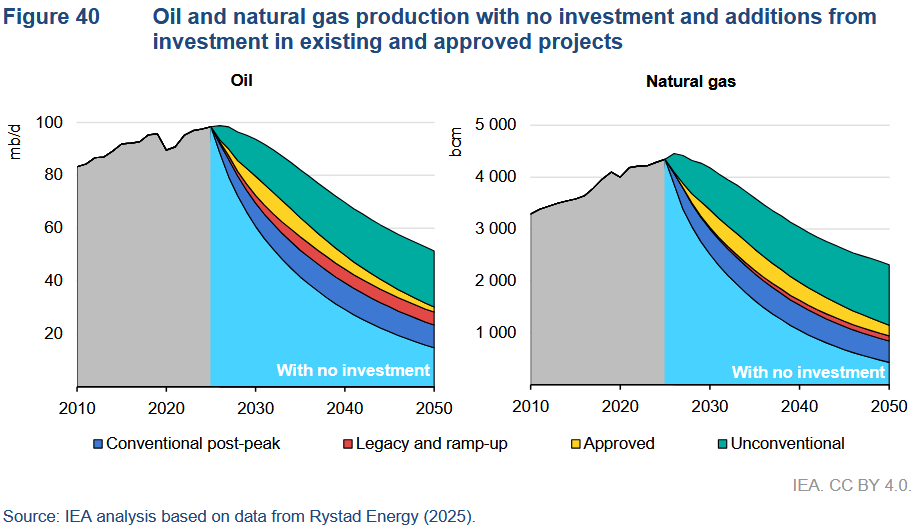

Or this:

Or this:

The big green blank space in the Ember chart above screams for a story to be told. Wind turbines and solar panels don’t just magically appear from nowhere — these technologies are not like oil found in the desert. Quartz rock, bauxite, iron, silver and a range of other metal ores, has to be mined and delivered to smelter first with trucks, shovels and ships consuming tons of diesel fuel every day. Smelting operations have to be powered by coal and natural gas to provide the high heat, the stable electricity supply and the necessary carbon atoms needed to remove all the oxygen locked up in these minerals (1) and finally to melt and shape them into form.

I’m sorry to be the party pooper here, but without fossil fuels there are no wind turbines or solar panels either. Nor bridges, dams, power lines or industrial civilization for that matter.

“Renewables” are in fact just a “smarter” way of burning those long dead plants and dinosaurs. Instead of using fossil fuels to generate electricity and motion at a 30% efficiency, we now increasingly convert coal, oil natural gas and Earth’s finite mineral reserves into solar panels and wind turbines hoping, that by the use of these devices, we could produce more energy than it took to make them. Making wind turbines and solar panels, however, cannot make us independent of fossil fuels, as the original image would imply — quite to the contrary: it just locks us more firmly in. So, just as we did not stop burning wood after coal came into the picture, or just as we kept burning coal after oil entered the scene, we will not stop burning fossil fuels — even if “renewables” were deployed en masse. With this fundamental piece of information missing from the Ember report, the whole electrotech vision turns into a navel-gazing exercise. To help us break out of this “electrotech” tunnel vision allow me to present you with a realistic version of the slide above:

The real reason behind the peak and decline of fossil fuel use, as I pointed out several times, is not electrification. Turning coal oil and gas into battery electric vehicles and photovoltaic cells is a response to the increasingly limited growth potential of said fuels as well as an attempt to move air pollution outside the city and other densely populated areas. Going electric cannot help us get rid of these polluting fuels — only resource depletion can do that. Here, I came across another new report — just released by the International Energy Agency (IEA) — pointing towards an accelerating decline in fossil fuel production from existing wells.

According to the findings of the IEA paper, without continued investment oil production would decline by 8% a year. This is the equivalent of losing more than the annual output of Brazil and Norway. Each year. Natural gas production would fall by an average of 9% annually, equivalent to total natural gas production from the whole of Africa today. Just by putting an end to drilling new wells, oil and gas would phase themselves out in almost no time. As we have seen above, however, that would not only put our ambitions towards an electrotech future on ice almost instantly, but would mean severe shortages from food (grown and delivered by diesel fuel) to clothes and just about anything we consume. In order to prevent this rather undesirable outcome nearly 90% of all annual upstream oil and gas investment since 2019 had to be dedicated to offsetting these accelerating production declines. Rather than to meet demand growth oil majors were literally focusing on keeping the lights on.

Natural decline rates were not so high always. As large conventional oil fields in America, Russia and the Middle East kept depleting at their slow 1–2% pace, and as demand doubled in the past couple of decades, we became increasingly reliant on unconventional sources of oil. These petroleum deposits, such as oil sands and shale (rock containing kerogen, a precursor to oil) or tight oil (oil trapped in low-permeability rocks like shale and limestone) and heavy oil (dense, viscous oil) all require specialized extraction methods. These sources often involved complex geological formations and advanced extraction technologies like hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and surface mining, making them more costly, environmentally destructive and energy intensive to produce than conventional oil.

The sharper natural decline rates observed now compared with earlier decades reflects this higher reliance today on unconventional sources, and the fact that we are now forced to replace slowly declining traditional super-giant fields with ever smaller and ever faster depleting unconventional ones. We are literally running the red queen’s race, and we are just a couple of years away from tipping over into a global decline in fossil fuel output.

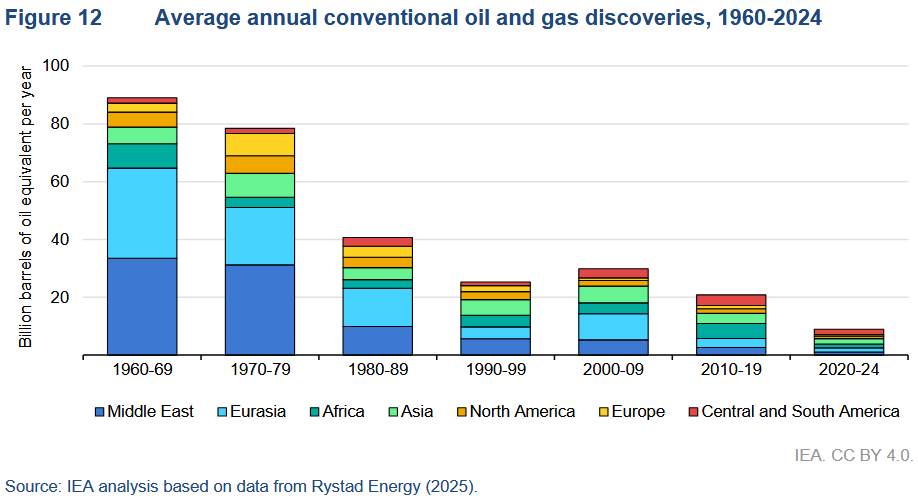

At the same time, and fully in line with the model runs shown above, we find less and less oil and gas every year. There is really not much left to discover: while we might and most likely find an oil field here and a field there in the future, these finds will be increasingly smaller and smaller:

Based on resource depletion the decline of modern industrial civilization is inevitable. Without fossil fuel energy (especially oil and gas) it will be impossible to maintain this high level of economic activity. In fact, and as the de-growth movement has long discovered, this is also a necessity to preserve as much Nature as possible for future generations. Even though the long decline in oil production will certainly mean a fall in material living standards — less gadgets, less trips abroad, smaller housing, less stable electricity supply etc. — not all of these changes will be for the worse. With less stuff to buy (and worry about) and less electricity to be spent on scrolling social media, real life relations, friendships and quality time spent together (or with a hobby) will all rise in value. This will be also a time for upcycling, tinkering and repair as well as for tool libraries and community gardens. Instead of falling into a depression and giving up on life I want you to think outside the tiny shoe-box you were put into as a child. Focus on the opportunities this future has to offer and find what you are best at — even if it means giving up your dreams of a corporate funded technutopia.

Until next time,

B

P.S.: Here is another fascinating read from Blair Fix describing our predator-prey relationship with oil — a well informed, highly intelligent analysis of our situation.

Thank you for reading The Honest Sorcerer. If you value this article or any others please share and consider a subscription, or perhaps buying a virtual coffee. At the same time allow me to express my eternal gratitude to those who already support my work — without you this site could not exist.

Notes:

(1) Yes, technically speaking we “could” replace fossil fuels with hydrogen in many of these applications, but hydrogen would have to be generated first by using massive amounts of electricity at a roughly 30% end-to-end efficiency. This method is so wasteful that it cannot even hope to compete with fossil fuels at present prices — let alone on a energy return on energy invested basis. With higher fuel prices however, demand for both energy and the products made and powered by that energy starts to drop like a rock. The combination of high prices and demand destruction demonstrably causes metallurgical plants and mines to close in droves, thereby removing the incentive to electrify these sectors. So while we can electrify low-heat, easy to automate sectors such as food processing, paper, textiles etc. the same could not be told about the processes providing this civilization with the raw materials and metals necessary to continue its existence.

B. I would love to hear you have a conversation with Nate Hagens. He is a humble polymath (a rarity) and was instrumental in “The Oil Drum” a publication analyzing the industry and resource extraction, working with major players in oil investments. Then, due to his awareness of similar conclusion to your own about the limits on the near horizon, shifted toward gaining an understanding ecological systems and began working in acedemia. For several years now he has put together a very intelligent podcast (The Great Simplification), most recently coming to similar conclusions as you express in your final paragraph. Very highly recommend looking into his work, if you are not already aware.

I did go to the trouble to review the presentation.

One slide in particular struck me… it showed "satellites" as part of the envisioned transition.

I guess Musk could integrate SpaceX and Tesla and make battery-powered rockets… how many 18650 lithium cells will it take to get a satellite into orbit? :-)

I'm concerned about all the comments that imply that "nuclear" will save our way of life.

By no means does nuclear energy escape the oil dependency seen in solar cells and wind turbines. Even small modular reactors will require mining (diesel-powered), refining (coal-powered), long-distance transport (diesel-powered)… not to mention cement and plastic.

And then, like solar panels and wind turbines, you have to decommission one generation and build replacements every 30-50 years or so, but nuclear has much more stringent requirements and expenses for decommissioning.

And in the end, like solar and wind, nuclear only provides electricity, which is incapable of producing the high temperatures and pressures required of modern refining and manufacturing.

If you don't think solar or wind can "save us", then keep in mind that the same restrictions apply to nuclear.