Everything Is Under Control… Until It Isn’t

The limits of self-organization and optimization

Despite legends stating otherwise, civilizations are not created consciously by any individual, nor they are destroyed by a single person (or even a group). Their birth, rise, and fall are a result of a group of people’s sustained self-optimization efforts towards a goal: ensuring stable food supply throughout the year or providing protection against marauders (among other things). Civilizations are much akin to living organisms in many respects. Complex societies metabolize raw materials and energy, and are driven by a desire to grow, as well as an instinct to survive. They are thus a part of, and entirely dependent on, their environment as any other living being. Should any civilization overshoot it’s environment’s capacity to sustain it (or Nature’s capacity to absorb the damage caused by its existence) it must suck in resources from elsewhere or adapt to the changed circumstances. That latter, however, is more than ‘problematic’ for a number of reasons.

Thank you for reading The Honest Sorcerer. If you value this article or any others please share and consider a subscription, or perhaps buying a virtual coffee. At the same time allow me to express my eternal gratitude to those who already support my work — without you this site could not exist.

On 23-24 April 2026, the World Adaptation Forum will take place in Budapest, where speakers from all across the globe will be discussing how the unraveling climate and the collapse of economic myths affect communities, and most importantly what are the paths towards resilience and renewal. This is not just another academic gathering—it is a space for truth-telling, deep listening and brave education. I will be attending as one of the moderators, but you can also join the forum online and hear from some of the leading voices, who are working tirelessly towards a state of planetary well-being and improving human futures. As a valued reader of this blog you can use a special coupon code (THS20) via this link (offering a 20% discount from the Online Access ticket type). Thank you for supporting this important initiative. And now…

In my previous two essays (Part I and Part II) I laid out the thermodynamic basis of every civilization: the need for high grade resources to grow and the acceleration in the rise of entropy the use of these high grade inputs cause—ultimately leading to the demise of every complex society. It follows from this argument, that there is no such thing as a steady (or equilibrium) state for any civilization: they either grow or begin to stagnate then decline. The only difference is how steep their rise and fall is. Since each and every one of them has tapped into a non- or very slowly renewable reserve of valuable inputs, the question of running low on one or more critical raw material was always a question of when, and not if. This is not to say that all civilizations collapsed due to resource depletion alone: there were many other factors putting an end to their existence much sooner than they could chop down the last tree standing, deplete the last mine, or erode the last inch of fertile topsoil. The rise in inequality, civil strife, elite mismanagement, war, pestilence, sudden shifts in climate etc. were all major contributing factors.

Our analogy between civilizations and living organisms stands for their decline as well. The rise in entropy (disorderliness) affects not only their environmental resources (leading to environmental degradation and resource depletion), but their internal structures as well. As empires grow, new infrastructure is built, new levels of hierarchy are established, specialization in various trades increases—all leading to a relentless rise in complexity1. Piling up complexity is not without its costs, though. It comes with greater energy and resource consumption, with each additional step increase requiring more and more inputs—while providing less and less benefits. At the same time the relentless rise in entropy starts to eat away the very foundations. Infrastructure ages and gets dilapidated. Adaptation skills atrophy as specialization requires less and less creativity. Organizations become bureaucratic, slow, multi-headed hydras—no longer capable to make (or carry out) coherent policy decisions, let alone solve the problems they were created to address. In other words: civilizations age just like other living beings.

Complex societies and other human organizations (such as corporations) are very good at solving problems related to growth and scaling up. (Those which are not, fail early and rarely get remembered.) Hitting limits to growth—be them internal due to a rise of complexity, or external due to the depletion of available resources—presents them with a challenge they are unable to meet: contraction. Again, our analogy with living organisms helps us to understand why. Think of an ageing elephant bull finding itself amidst a long term shift in rainfall patterns, requiring it to move a huge distance to find greener pastures. It’s bones and joints are aching. It’s cognitive skills are in a decline. It no longer knows which direction to go, where to find more food and water, or how to get there. It’s stuck in place and now starving. It’s facing the same predicament ageing civilizations do: unable to feed itself, and unable to change its circumstances.

Neither living beings nor civilizations can shrink indefinitely. Sure, they can shed weight, or even consume parts of themselves in a process called ‘autophagy’ during the final stage of starvation. However, neither can go back to their newborn size. Bones, brain mass, blood vessels, intestines etc. were all scaled up a long time ago to meet the demands of a large, mature body. Roads, canals, cities, administrative organs, the military etc. were similarly scaled up to meet the demands (and to fully exploit the potential) of a vibrant society full of energy and having high grade natural resources at its disposal. Each of these organs and organizations (as well as the physical infrastructure itself) have their own needs and demands, however, and cannot shrink below a certain size without risking their own existence. Mammals, for example, can survive 25-30% weight loss (we are talking healthy, not overweight animals here), but at such scale of deprivation death is a more likely outcome. Similarly, there is only so much complexity2 a society can shed before going through a radical, uncontrolled simplification—a.k.a. collapse—due to a relative lack of energy, food and other resources.

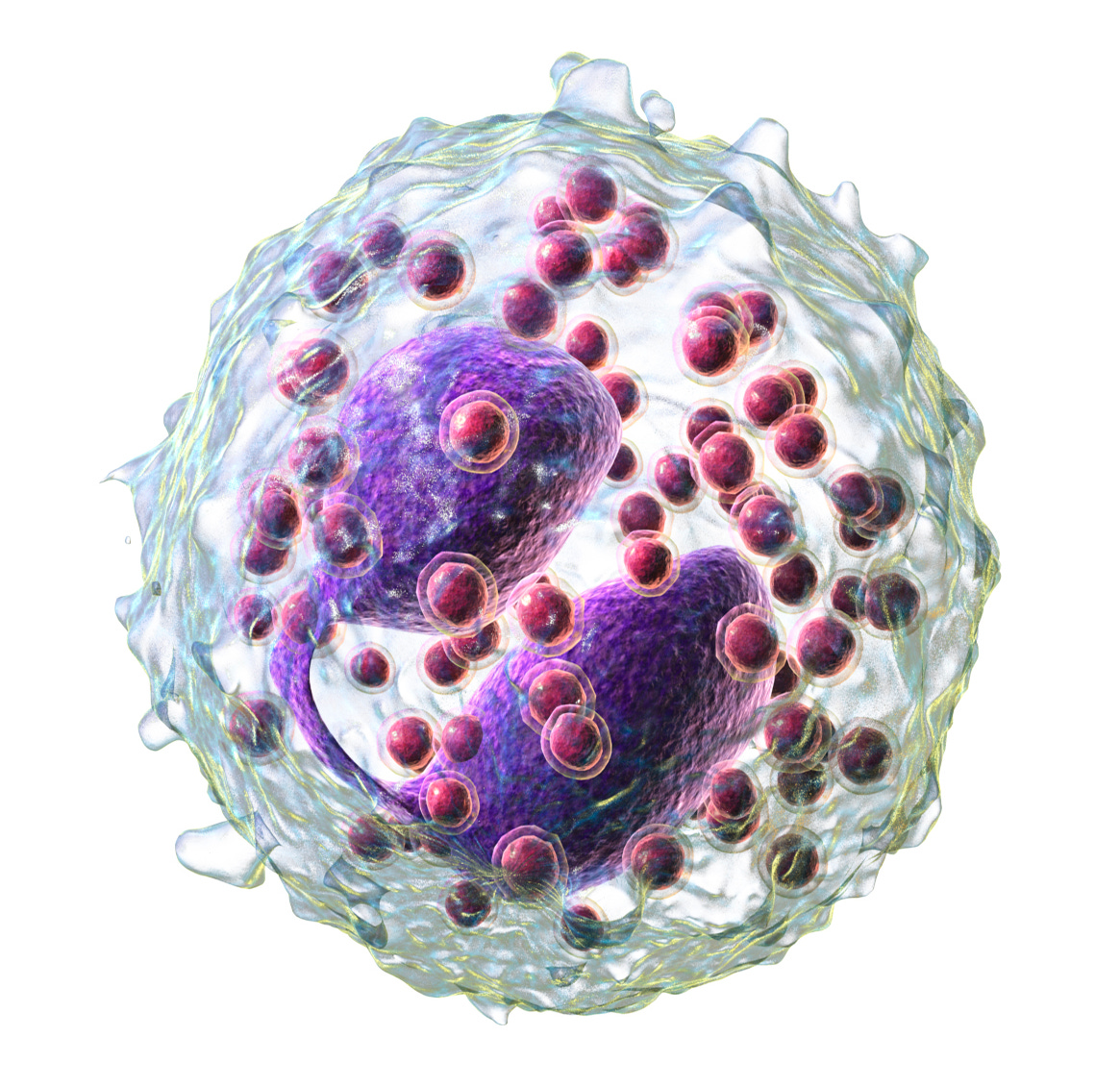

Before death or collapse happens, though, both living beings and societies switch to self-preservation mode and optimize their internal workings to survive what both believe to be a “rough patch” or “just another temporary scarcity.” Nutrients and energy are diverted to sustain vital organs. Reserve stores of nutrients (in the form of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins) are utilized to compensate for the lack of nutritional intake. Metabolism is switched off, and the body starts to recycle its own building blocks (amino acids) to upkeep a healthy brain and heart function as long as possible. Meanwhile the immune system gets a boost: old, damaged white blood cells are destroyed and new, more efficient immune cells are generated with the aim of clearing cellular debris and strengthening immunity. Autophagy, at first, revitalizes the body and helps to get rid of waste. Beyond a certain point, however, it becomes destructive and causes permanent damage.

Our civilization has, I believe, arrived at the onset of this advanced autophagous stage. The world economy seems to have forgotten how to grow: global material growth slowed down then reversed in the late 2010’s and early 20’s. Real increases in material prosperity for the average citizen were replaced with an insane rise in stock valuations and financialization, accompanied by both private and government debt levels shooting through the roof. Increases in complexity are now beyond diminishing returns, our innovations now steadily produce net negative results to society. Think, for example, AI and the electricity cost, water consumption and emissions increase the deployment of data centers caused around the world… And for what benefit? To get rid of more workers, who in turn no longer consume as much…?

The “problem” can be traced back to the insane rise of entropy both within and around the economy. Metal ore grades are falling, together with the energy return on energy invested in the fossil fuel industry, as high grade easy to get deposits of both metals and coal, oil, and gas deplete. The system began to self-optimize: coal is being replaced by natural gas, as mining and delivering coal requires huge amounts of diesel fuel—something we can no longer make enough of and have nothing to substitute with at scale. In fact, 40% of all goods shipped worldwide (and thus 40% of shipping fuel consumption) comes from delivering coal, oil and gas to customers. Switching heavy and bulky coal to pipeline gas (but not LNG!) thus comes at a significant liquid fuel saving potential. There is no central planning in this, mind you, just good ol’ economics: coal producers and buyers can no longer afford the fuel and power needed to continue with their operations… A “problem” made worse by mines around industrial centers running out of close-to-surface, easy-to-get coal, another sign of increasing entropy (beyond the rise in temperatures the burning of all that carbon caused). However, with a steady rise in the energy needs of oil and gas drilling, as well as an accelerated depletion of existing fields, ditching coal was but a temporary measure.

The industrial system is not ready to give up just yet. Instead of adding more fossil fuel generation capacity (which, as we have seen, is a futile effort) it increasingly turns towards adding more “renewable” sources of electricity. Even though the mining, manufacturing, delivery and construction of solar and wind farms takes large amounts of fossil fuels, the global energy system as a whole can still generate more power with them in total than by simply burning all that coal, oil and gas in a thermal power plant. Just like installing a heat pump, which taps into the heat stored in the environment by using a little electricity, the global energy system learned how to tap into the flow of solar energy hitting Earth every day, by using “some” fossil fuels in excavators, dumpers, ships and metal smelters. Take note, however, how this is not a solution to the depletion of fossil fuels, nor the lack of transportation fuels, as the vast amounts of coal delivered on barges and trucks are now replaced with a similar amount of ores delivered into smelters. It just a “smarter” way of using our limited set of resources: getting more electricity out of the system, before it runs out of stuff (such as copper), or the energy (diesel fuel) needed to continue building it out at such a scale. As a sign of things to come, the global “energy transition” is already threatened by critical transformer shortages—and we haven’t even passed peak copper yet. Again, this is self-optimization—not salvation—in the face of resource scarcity. Prediction: the coming decline in global fossil fuel production will eventually cause a decline in the manufacturing of solar panels and wind turbines as well—albeit with a considerable delay, due to further rounds of optimizations.

Another interesting facet of hitting peak material consumption, is how facilities required to process raw materials are experiencing a worsening overcapacity issue. Countries, for example, just kept adding coal power plant capacities, even as their coal production approached its peak, resulting in a predictable burst in excess capacity as coal production turned into decline. Similarly, global copper smelter capacity just keeps increasing, even as a worldwide peak in copper ore production is clearly on the horizon. And now that global steel production has peaked in 2021 (as of 2025 world steel production was still in a post peak decline), an increasing number of blast furnaces have ended up being underutilized. Who could’ve thought…? The problem is, the system is unable to plan on a long enough horizon (i.e. beyond a few years), and tend to be overoptimistic rather than cautious. Cue: China’s Steel Transformation, or how the largest manufacturing power in the world turns away from blast furnaces and seeks to build more electric arc furnaces instead.

Although it’s sold as a measure to lower CO2 emissions, China’s steel transformation is yet another sign of autophagy: instead of creating and building more stuff (in which crude steel is vital), it seeks to recycle products and infrastructure built a long time ago. See, blast furnaces—burning tons of coal—are used to make virgin steel used in building bridges and other infrastructure projects, where durability and high structural strength is key. Electric arc furnaces, on the other hand, use scrap metal as an input, and thus produce lower quality steel (due to the many impurities and unknown / variable chemical composition of scrap steel). A decline in blast furnace output (and the resultant overcapacity issue) is thus a clear sign of a structural decline in construction—and signals the onset of autophagy. (For the record: the US has already transitioned into this phase decades ago, and resorts to imports from China and elsewhere when it comes to high grade steel variants.)

Now, if you allow me to overstretch the analogy a little, the link between the end to material growth and the purge in China’s military top rank is hard to dismiss here. Just as the body destroys old, damaged white blood cells to generate new, more efficient immune cells when faced with scarcity, the lack of meaningful economic growth coupled with a deepening population, debt and deflationary crisis has led to similar measures from the central government. I mean, when top leaders fear for their positions, as their legitimacy (rooted in infinite growth on a finite planet) is shaken, they start to get rid of dissenting voices and potential threats from within the power structure. But hey, the same applies to companies as well: as growth stalls, a change in management is all but guaranteed, often along similar lines. And the more stubborn stagnation (let alone decline) turns out to be, the more frequent these changes will become… The rate of change in the economy (growth) is in an inverse relationship with the rate of change in politics, it seems... So, expect more of the same as stagnation continues, and growth slowly turns into decline.

In fairness, the situation is much-much worse over the Pacific, in the U.S., and on the other end of Asia: Europe. The decline—and now the falling apart—of the Western world order can also be traced back to the block’s long ongoing economic decline, and ultimately: a rapid rise in entropy. Coal production is in a terminal decline across the entire West, and oil and gas production is peaking, too. The US and Europe has been already largely deindustrialized, and became utterly dependent on China and the rest of the world for key inputs. The EU is in a particularly bad shape, as high energy prices have led to not only a sharp decline in steel output, but a collapse of the block’s aluminum production as well, threatening the viability of what remains of it’s industry (including aerospace and defense). But the rise in entropy is not limited to industry alone, it has become palpable all across the board: from education to management and leadership positions.

The U.S.’s retreat into the western hemisphere follows the same logic. America can no longer afford to be strong everywhere—it must “share the burden” of maintaining its primacy with its “allies and partners”. And while many believe this to be but a temporary necessity in preparation for a return to “the world’s only hegemon” position, in fact, it might turn out to be permanent—with no chance of a return to “normal.”3 Again, yet another example of the U.S. entering a more serious phase of autophagy… With that said, there is nothing personal in this: the system doesn’t plan ahead, and it badly sucks at explaining what it does and why it does it. The steady fall in the quality of leaders it produces, however, signals that what the entire West is going through is not just a “rough patch”, or something which “could be turned around”, but a terminal decline. What China has just started to experience with the structural slow down of growth and the onset of economic stagnation, is already a reality in the West since decades now.

Make no mistake, I’m not rooting for the fall of either side. I really wish that this transition from global economic growth into a highly uneven, but permanent, decline could be managed peacefully. The world still has plenty of resources left to feed, house and clothe its residents (at least for a while and as climate change permits), but a peak in material and energy output will slowly make previous levels of consumption and waste impossible. Economic models, trade and financial systems are badly in need of a major overhaul to reflect this reality. We are, on the other hand, dealing with extremely short sighted, self-optimizing systems here, producing an exponential rise in entropy, alongside more and more erratic, incapable and honestly delusional leaders all across the world. People, who grew old seeing nothing but growth and a rise in prosperity—something which is definitely approaching its end worldwide. How will they react when a major financial crash arrives at their doorstep, or when one of their military adventures goes terribly awry, is anyone’s guess at this point. Well, as the saying goes:

Everything is under control… Until it isn’t.

Until next time,

B

Thank you for reading The Honest Sorcerer. If you value this article or any others please share and consider a subscription, or perhaps buying a virtual coffee. At the same time allow me to express my eternal gratitude to those who already support my work — without you this site could not exist.

Joseph A. Tainter: The Collapse of Complex Societies

Exactly how much complexity a society can shed before collapsing can vary greatly from case to case, depending on the level of complexity and the availability of fall-back options. Note, how collapse in this sense means political-economic collapse; followed by a long tail of technological and population decline.

The irony of U.S. retrenchment in the face of hegemonic decline is hard to miss here—the situation is not at all different from the withdrawal of Roman forces from Britain some sixteen hundred years ago. Read Tim Watkins’s excellent piece on how that could played out.

For some time now, I have been promoting hypercomplexity in my comments on the Web, my books and my own Substack. Those who read my writings know this. I have gotten some pushback as well as arguments from the troll populace, but it is still to my advantage to make this delineation, something B does not do yet. YET! He may get there soon enough since he is an astute analyst and is able to follow where his own argument leads.

In a nutshell, the US and UK are not just complex societies; they are hypercomplex in their growth economies, which also translates into their societal functions. This is based on the acceleration of acceleration of their growth models (the third derivative, or "jerk" in calculus parlance) and comes from the NECESSITY to go faster and faster just to stay in place on a treadmill that is not just increasing in speed, but actually rising in its incline, so the speed at which the economy and society in general is moving needs to constantly accelerate its acceleration. Other countries, like France and Germany are accelerating their growth economies but not increasing their acceleration. In fact, they are contracting AND they seem to be managing their contraction. (And yes they could do a better job of it. C'est la vie.

The US and UK need everyone to not only consumer more and work more, but also increase their consumption and work at a constantly increasing pace. This argues against their ability to work within any form of limits and manage their coming contraction. Therefore they will just crash.

I have mixed feelings about the analogy of an economy or a society to an individual organism. It is well known in the study of ancient cultures that people just vote with their feet rather than go down with the ship. Also, the autophagy example is suspect too, as autophagy is a regular process that eats up the depleted cells and the toxins that have been freed. In B's analogy, the autophagy process eats up everyone.

In real terms, we just don't know how this collapse will play out beyond some broad strokes. The best adaptation is to be adaptable. Since industrial agriculture depends heavily on globalized phosphorus reserves that require control of source, plus massive amounts of fossil fuels to build the tractors and combines, plus massive amounts of fossil fuels to manufacture fertilizer, plus massive amounts of fossil fuels in production and transport, it is unlikely that die-off can be put off in any appreciable manner. In other words, as many of us have been saying for sometime; it is not a question of IF there is a die-off. It is a question of WHEN. Then it is all a crap shoot and no amount of airy-fairy design work will see you through. You will have to adapt to survive.

What I and many other sustainable farmer types have been doing for some years is developing alternate strategies. These can be tested right now AND they actually provide a favorable EROI for food production. It is not a question of whether it is sustainable in some rarified academic treatise; it is a question of how many people we can save now and in the future.

I get a lot of flack from computer jockeys who want to argue about what sustainable means or if agriculture is "bad" or some other bullshit. What I work on is growing potatoes, beans, wheat, etc. with lowered energy inputs. Once you get on that particular train, you have more places to jump off before the train goes over the cliff.

Observation about the unsustainable push for renewable energy. It has been mentioned that building out renewable energy infrastructure consumes vast resources and we don’t have enough energy nor resources to fully transition to renewables. Now, consider that every piece of that renewable energy generation will need complete replacement within 50 years.

If renewable energy can’t be built out once, then how will it be completely replaced every 50 years? And don’t say it will be “recycled”. Some of the metals will be recycled, but even that takes energy. Solar panels can’t be recycled, nor can wind turbine blades, etc. Realistically, just a tiny percentage of the energy and resources which went into building that renewable infrastructure will carry forward to its replacement.